|

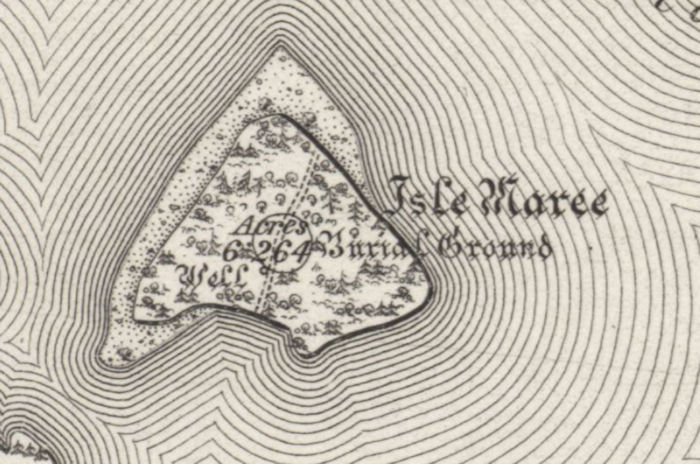

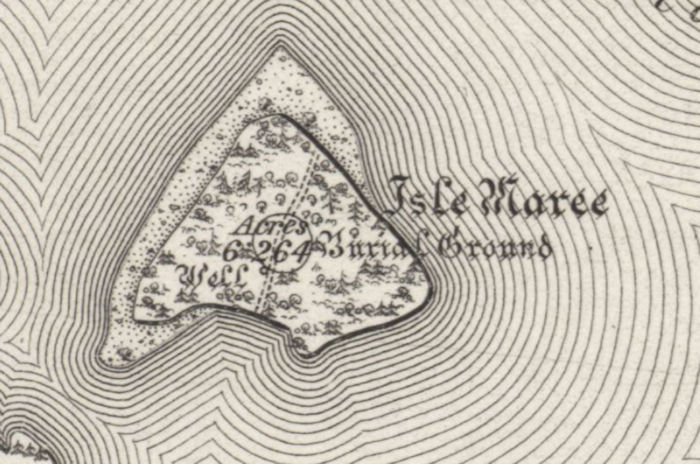

Dedication: Saint Maelrubha Location: Isle Maree Coordinates: 57.69313N, -5.47313W Grid reference: NG931723 Status: dry? Heritage designation: none |

|

Dedication: Saint Maelrubha Location: Isle Maree Coordinates: 57.69313N, -5.47313W Grid reference: NG931723 Status: dry? Heritage designation: none |

Saint Maelrubha was a 6th and early 7th century missionary, who travelled to Scotland in the late 6th century from Ireland. Initially, Maelrubha was educated at Bangor Abbey in County Down, Ireland, which had previously been founded by St Comgall, Maelrubha's uncle. In 671, aged 30, he left Ireland for Scotland, where he proceeded to found a famous monastery at Applecross, which later became the centre of his cult, and was second only in repute to Iona. According to local legend, Maelrubha once lived as a hermit in a cell on Isle Maree; after his death in 722, the island reportedly became the residence of a priest, and a chapel or church of the saint also existed in medieval times by the head of Loch Maree. In fact, it is quite likely that Maelrubha did indeed spend some time as a hermit on the island.

Isle Maree seems to have been frequented by pilgrims in the medieval period, the majority of them likely travelling to obtain a cure from the holy well, which was particularly esteemed for its efficacy in curing madness. The ritual that was first described in the late 18th century by Thomas Pennant is probably identical, or almost identical, to the one that would have been performed in medieval times. To begin, the "patient" would leave an offering of money on the island's altar, and drink a portion of water from the well, before returning to the altar to leave a second offering. Then, the patient would be dipped in the waters of Loch Maree three times, and this process would be repeated daily until the lunatic was cured. According to Sketches of Scenes in Scotland (1834), this ritual was often "performed by the light of the clear full moon". Thomas Pennant, who visited the island himself, described the ceremony in 1774 in A Tour in Scotland:

|

A ſtump of tree is ſhewn as an altar, probably the memorial of one of ſtone; but the curioſity of the place is the well of the ſaint; of power unſpeakable in caſes of lunacy. The patient is brought into the ſacred iſland, is made to kneel before the altar, where his attendants leave an offering in money: he is then brought to the well, and ſips ſome of the holy water: a ſecond offering is made; that done, he is thrice dipped in the lake; and the ſame operation is repeated every day for ſome weeks: and it often happens, by natural cauſes, the patient receives relief, of which the ſaint receives the credit. |

Pennant also mentioned another tradition that the quantity of water in the well would affect the likelihood of a cure being obtained. According to him, the water level would allow pilgrims to determine "the diſpoſition of St. Maree": if the well was full of water, then it was believed that "he will be propitious", although if the water level was very low, then pilgrims would "proceed in their operations with fears and doubts".

It is not clear when exactly the ritual fell out of use. The site was certainly continually visited by pilgrims into the late 19th century, but whether they performed the ceremony is uncertain; it is quite likely that Victorian pilgrims would only have performed a simplified version of the ritual, as happened at St Tegla's Well, in Denbighshire. Indeed, although John Macculloch, in The Highlands and Western Isles of Scotland (1824), claimed that "the practice has passed away", coins and scraps of patients' clothes were still being attached by pilgrims in the early 19th century. This tree seems to have replaced the altar that Pennant described, perhaps after the "ſtump of tree" had rotted away; nonetheless, the tradition of leaving monetary offerings persisted, with coins being hammered into the tree's bark.

By 1861, the well had dried up, and it may have been this that caused the cessation of pilgrimage to the well. It is not clear what made the spring dry up, but it was still dry when Arthur Mitchell, who described the site in The Past in the Present (1881), visited the island in the late 19th century, by which time the tradition seems to have died out:

|

The celebrated well is near the shore. At the time of my visit it was dry, and full of last year's leaves. It is a built well, and the flat stone which serves for a cover was lying on the bank. Near it stands an oak-tree studded with nails. To each of these was originally attached a piece of the clothing of some patient who had visited the island. One had still fastened to it a faded ribbon. Two bone buttons and two buckles were also found nailed to the tree. Countless pennies and half-pennies had been driven edgewise into the wood - over many the bark was closing, over many it had already closed. |

It appears that the custom of leaving offerings on the tree had lost its true meaning. When Queen Victoria visited the island on the 16th of September, 1877, she herself hammered a coin into the bark of the tree, although she did not perform any other parts of the ritual, and the well was dry. Her own account of the visit was published in 1884 in More Leaves from the Journal of a Life in the Highlands:

|

The boat was pushed on shore, and we scrambled out and walked through the tangled underwood and thicket of oak, holly, birch, ash, beech, etc., which covers the islet, to the well, now nearly dry, which is said to be celebrated for the cure of insanity. An old tree stands close to it, and into the bark of this it is the custom, from time immemorial, for every one who goes there to insert with a hammer a copper coin, as a sort of offering to the saint who lived there in the eighth century, called Saint Maolruabh or Mulroy... We hammered some pennies into the tree, to the branches of which there are also rags and ribbons tied. |

The well has always been marked on historical Ordnance Survey maps, although it is not marked on maps today. The Canmore database does not provide a record of its current condition, and it remains uncertain what state of repair the well is in.

|

Access: The island is only accessible by boat. |

Images:

Old OS maps are reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

Copyright 2025 britishholywells.co.uk