|

HOME - ENGLAND - OXFORDSHIRE

Dedication: Saint Edmund of Abingdon Location: St Clements Status: lost/destroyed? |

St Edmund of Abingdon, also called St Edmund of Canterbury, was a late 12th and early 13th century scholar. He was born into a wealthy merchant family at Abingdon, only about 6 miles from Oxford, in or around the year 1174, reputedly on the feast day of St Edmund the Martyr (the 20th of November), an East Anglian king from the 9th century after whom Edmund of Abingdon may have been named. Edmund of Abingdon attended Oxford University, where he apparently took a vow of perpetual chastity, before travelling to Paris and studying there for some time; he later lectured in both places, but is specifically associated with Oxford and Salisbury Cathedral, which he was once canon of. After being promoted to the position of Archbishop of Canterbury in 1233, he clashed with Henry III, and even went as far as threatening to excommunicate the king from the Catholic Church. In 1240, Edmund fell ill and died in France, and was subsequently interred in Pontigny Abbey in Burgundy; he was officially canonised only seven years later, in light of several miracles that had apparently occurred at his tomb.

Although none of Edmund's relics ever made their way to Oxford, his cult evidently still developed in the city very quickly. Stories involving miracles supposedly effected by Edmund in the area began to circulate, and he became associated with St Edmund Hall, now a college. It is probably because of this that St Edmund's Well came into existence: the saint was closely linked to Oxford, and yet pilgrims in the area had no way of venerating him, because his relics were held in France, and not a single church in the city bore his patronage. The holy well thus became the only place in England where admirers of Edmund, who appears to have been quite a popular figure in life, and certainly in death, could venerate him.

It is, then, no surprise that St Edmund's Well became one of the country's most popular holy wells within fifty years of its patron's death. The site's fame spread as far as Lincolnshire (and likely much further), where it came to the attention of Oliver Sutton, then Bishop of Lincoln, who appears to have had a powerful but strange contempt for holy wells that was certainly ahead of his time; other sites that he targeted include St Laurence's Well at Peterborough. It is worth noting that the Diocese of Lincoln then included Oxford, which only became its own bishopric in the mid-1500s. In the eleventh year of his leadership, 1291, Sutton issued a mandate to the Archdeacon of Oxford commanding that pilgrimage to "fontem beati Edmundi" be completely banned, on fear, much in the manner of St Edmund himself, of major excommunication (a sanction usually reserved for the punishment of very serious offences) from the Catholic Church. Simon Gunton included a full transcription of the edict, preserved in the "Register of the Acts" of Oliver Sutton, in his History of the Cathedral Church of Peterburgh, published in 1686:

|

Ad Audientiam noſtram nuper certa relatione pervenit, Quod nonnulli juxta ſuarum mentium inconſtantiam quaſi vento agitati a cultu fidei temere deviantes, locum quendam in campo juxta Eccleſiam Sancti Clementis extra Municipium Oxon. fontem beati Edmundi vulgariter nuncupatum, veluti locum ſacrum venerari, illumque ſub ſimulatione ſacrorum Miraculorum quae perpetrata confingunt ibidem cauſa devotionis erroneae frequentare, ac populum non modicum illuc attrahendo hujuſmodi figmentis dampnatis decipere imo pervertere noviter preſumpſerint, errorem Gentilium inter Chriſticolas introducere ſuperſtitioſe conando. Nos vero hujuſmodi incredulitatis perſidiam, veluti contra ſidem Eccleſiae & Doctrinam Apoſtolicam ne corda renatorum caligine haereticae pravitatis obducat temporis per proceſſum, ſi forte radicari & germinare zizania permittatur, tortuoſe ſerpente virus ſui cautius miniſtrante, ſomentum eliminare & prorſus amputare deo propitio volentes, Vobis ſirmiter injungendo mandamus quantenus in ſingulis Eccleſiis intra Miſſarum ſolempnia, & locis aliis Archidiaconatus veſtri in quibus videritis expedire per vos & alios firmiter inhibeatis ne quis ad dictum locum cauſa venerationis ejuſdem de cetero convenire & illum ſuperſtitioſe frequentare preſumat ſub pena Ex-communicationis Maj. onmes & ſingulos contra hujus inhibitionem ſcienter temere venientes dicta ſententia comminata ſolempniter in genere innodantes, donec de culpa contriti beneficium abſolutionis meruerint obtinere. Translation: A certain report has recently reached our Audience, that some, according to the inconstancy of their minds, as if driven by the wind, recklessly deviating from the worship of the faith, venerate a certain place in the field near the Church of St. Clement outside the Municipality of Oxon, commonly called the Fountain of Blessed Edmund, as a sacred place, and frequent it under the pretence of sacred Miracles which they pretend to have been perpetrated there, for the sake of erroneous devotion, and by attracting a considerable number of the people there with such damned fictions, have newly presumed to deceive, nay, to pervert them, by superstitiously attempting to introduce the error of the Gentiles among Christians. We, however, wishing to eliminate and completely cut off, by God's mercy, the persecutory nature of this kind of unbelief, as if contrary to the Church and the Apostolic Doctrine, lest the hearts of the reborn be covered with the darkness of heretical wickedness through the course of time, if perhaps the tares are allowed to take root and germinate, with the tortuous serpent's venom ministering more cautiously to itself, we firmly enjoin upon you that in each Church during the solemnities of Mass, and in other places of your Archdeaconry in which you see fit, you and others firmly forbid that anyone should presume to meet at the said place for the sake of veneration and to frequent it superstitiously, under penalty of Major Excommunication, all and each one, knowingly and rashly coming against this prohibition, solemnly binding themselves in the family with the said threatened sentence, until, having been contrite for their guilt, they have merited to obtain the benefit of absolution. |

The cult of St Edmund's Well must have been very strong, because the site appears to have survived this ruling, unlike St Laurence's Well at Peterborough, completely intact. Whether Sutton's efforts affected the number of pilgrimages made to the well at all is unclear, but he certainly did not severely damage its popularity. It is interesting to note, however, that, at least according to the Survey of Oxford, which was compiled by Anthony Wood between the years of 1661 and 1666, the spring was most popular "in the raignes [sic] of Henry III and Edward I". Edward I died in 1307, just after Sutton's orders were issued, and Henry III was, of course, his predecessor, which would suggest that the site's fame decreased somewhat following the above orders. This information is also useful because Henry's reign only lasted until 1272, meaning that the well must have been in existence as early as the 1270s.

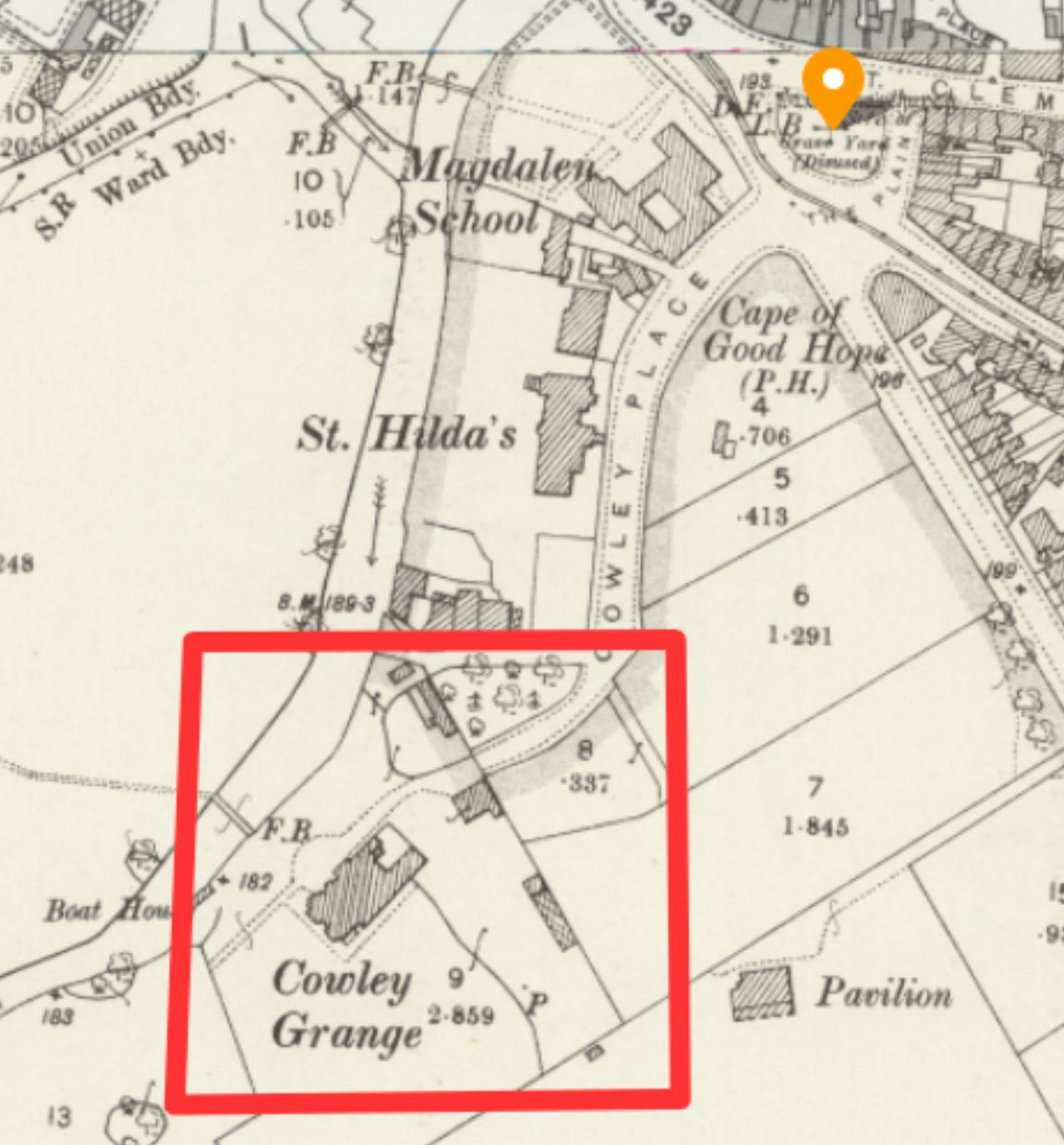

Nevertheless, the well was still in existence, and certainly well-known, in 1524, when it was mentioned in the "Journal Book of the Expences of all the Buildings of Christ Church College". These records were transcribed and published in the first volume of Collectanea Curiosa (1781), by John Gutch, who claimed to have received the information from "Mr. PORE of Blechinton". According to the accounts, a certain "Thomas Hewiſter" had received "xxxviiis" (around £630 today) for the "carriage of 143 loads" of gravel "from St. Edmund's well to the work"; the records state that this "work" was the "making, planking and rayling" of a new bridge, which stood "over the water in Cowley Mead" and was located "between St. Edmund's well and the eaſt ſide of the ſaid College" (this being, if the Rev. J. Peshall, writing in The Antient and Present State of the City of Oxford in 1773, is to be believed, "Cardinal Wolſey's" college). In addition to this, workers were apparently engaged in the "making of two new gates", one of which was placed "near unto St. Edmund's well".

Throughout the medieval period, and particularly during the latter half of the 13th century, the waters of St Edmund's Well are said to have been renowned for effecting miraculous cures. Anthony Wood, in his Survey of Oxford, asserted that the "curing of wounds and recovery of maladyes and sicknesses" could be achieved by pilgrims in two different ways: by either "drinking the water therof", or by "bathing therin" (if the latter is true, then the spring must have been contained in a suitable structure to allow for full immersion to take place). Additionally, Robert Plot claimed that locals once "made vows, and brought their alms and offerings" to the well, in The Natural History of Oxfordshire (1677). More intriguing than this, however, is the unusual medieval legend that became associated with the holy well: according to tradition, St Edmund, whilst in Oxford, often experienced "visions" of the Virgin Mary and God during his regular "walkes of recreation" (as Wood puts it) in the fields surrounding the city. In Remaines of Gentilisme and Judaisme, written between the years of 1686 and 1687, John Aubrey recorded a legend that linked these traditions to the holy well, notably that St Edmund's Well was the place at which Edmund "did sometimes meet & converse with an Angel or Nymph". Anthony Wood went as far as to assert that "Jesus Christ appeared to him" on one of these occasions. This is almost certainly a medieval tradition, perhaps one that was invented in the 13th century to explain the origin of the holy well, and to substantiate evidence of an authentic link to the saint, possibly in retaliation to Bishop Sutton's decree.

It is not easy to ascertain whether these traditions died out immediately after the Reformation, or whether they survived for some time afterwards, but the nature of the holy well's destruction suggests that St Edmund's Well had become almost completely forgotten by the early 1600s. Anthony Wood explained that the spring "was open till Milham bridg fell downe", and then, "by degrees for want of recours therto in summertime", the well was "stopped up". The approximate date of the well's destruction, or, rather, disappearance, can be deduced from the remarks of John Aubrey, who reported that St Edmund's Well had been "stopt up since the warres", "warres" here referring undoubtedly to the Civil War, which took place between the years of 1642 and 1651.

Unfortunately, the well appears to have completely vanished very quickly, and the only surviving records of its exact location are rather vague. Anthony Wood recorded that St Edmund's Well was "on the south side of S. Clement's Church and neare to the ford or water called Mill Ford or Cowley Ford which leadeth into Cowley Mede", and Robert Plot confirmed this when he wrote in 1677 that the spring was once situated "in the field about a furlong S. S. Weſt of the Church". Further evidence for the exact location of the well is provided by the existence of "St. Edmund's Well Furling", "furling" probably being a corruption of "furlong", a patch of land situated just south of the original site of St Clement's Church. It is also clear from all descriptions that the spring was located within the bounds of St Clements parish.

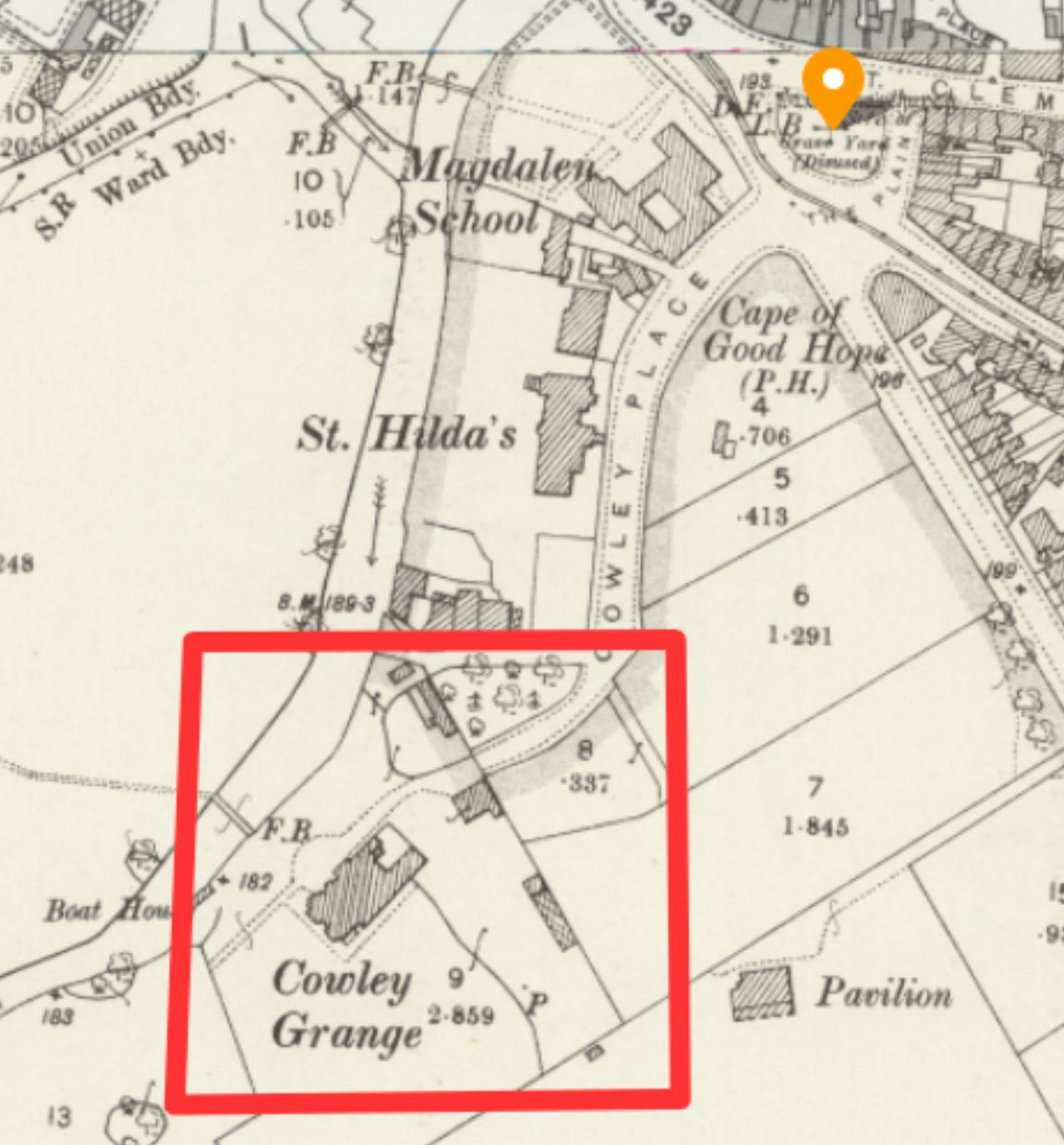

The 1886 OS map of the area marks "Mill Ford" at SP5213405853, just south west of what is now St Hilda's College; it is surely no coincidence that this ford was located approximately a furlong south west of the original site of St Clement's Church. This suggests that the holy well was located on the eastern side of the River Cherwell, just south of St Hilda's, which is corroborated by the fact that this would place the site both within the parish of St Clements, and on the edge of "St Edmund's Well Furling". Old Ordnance Survey maps, of course, do not mark any springs or wells in this area, which is no surprise given what is said to have happened to the site. Rather oddly, James Ingram, writing in Memorials of Oxford in 1837, described a "well of good spring water" at this location, which he claimed was known as St Edmund's Well, and was "never known to fail in the dryest season"; Ingram was probably incorrect in his claims, which contradict all other sources that I have come across.

|

Images:

Old OS maps are reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

Copyright 2025 britishholywells.co.uk