Image capture: July 2024 ęGoogle |

Dedication: Saint Cadfan Location: Tywyn Coordinates: 52.588313N, -4.087533W Grid reference: SH586009 Status: destroyed |

Image capture: July 2024 ęGoogle |

Dedication: Saint Cadfan Location: Tywyn Coordinates: 52.588313N, -4.087533W Grid reference: SH586009 Status: destroyed |

St Cadfan is said to have been the son of the 5th century St Gwen Teirbron (this literally translates as "Gwen of the three breasts", which, according to popular tradition, she did in fact have), and the cousin of St Derfel. He established the church at Llangadfan, which boasts his only surviving holy well, Ffynnon Gadfan, and also founded a clas (an early form of a monastic establishment in Wales that predated the Norman Conquest) at Tywyn, of which he became the first abbot. He later went on to become the abbot of Bardsey in around 516. He is said to have travelled to Tywyn, along with twelve other saints, from Brittany.

Ffynnon Gadfan itself was a chalybeate well (meaning that its water contained a high concentration of iron). It likely dated from the time of St Cadfan, the 6th century, and possibly had some association with his clas, as it almost certainly had later with the current parish church. During the Medieval era, its reputation as a healing well spread far, and it was one of those very unusual holy wells that maintained its reputation even after the Reformation. According to the Coflein database, a document (unfortunately the document is not named, and I was unable to find it) of 1535 recorded that the well lay within the churchyard, which is no surprise, given its proximity to the church. It evidently suffered during the Reformation, as, in 1672, or thereabouts, it was recorded that:

|

In the churchyard of Towyn Parish lyeth a decayed chappell known as St. Cadvan's chappell, or its scite. |

The well was, in fact, so famed in the Victorian era that it is difficult to imagine just how popular it must have been prior to the Reformation. Many Victorian authors refer to the well in their gazetteers or, more commonly, travel guides, and it appears that "St Cadfan's Wells" became a tourist destination, as well as one for pilgrims. During the Victorian era, the well was especially noted for being effective in the curing of rheumatism, scrofula and various skin problems, and it is very likely that this tradition is a remnant of a much earlier Medieval one. It is most unusual, however, that St Cadfan's Well never became, so to speak, secularised: in most cases, by the Victorian era, any belief in the healing powers of water, which had, prior to the Reformation, been associated with Christianity, mostly moved away from religion and entered into the realm of very dubious alternative medicinal treatments, like the Malvern "water cure"; instead, the well was still a small centre of pilgrimage, and it appears that there was still a very much religious aspect to the well's popularity. Rev. Elias Owen, in a part of Collections Historical and Archaeological Relating to Montgomeryshire and its Borders, published sometime after his visit to the site, illustrates its reputation for healing:

|

St. Cadfan's Well, Towyn, had on its walls, when I visited it last year, 1892, a single crutch, the rest - and there were once many of them - had been removed. |

Indeed, it was evidently so popular with Victorian pilgrims that, at some point, the landowners decided to build a bath-house on the site to facilitate the visitors. It seems that this was an ingenious move, and thereafter it became one of the most favoured tourist attractions in Tywyn. There was evidently also some sort of ritualistic element to bathing at the well; according to volume 25 of The Penny Post (1875), it was believed that cures could only be effected at certain times of day:

|

Near Towyn, North Wales, there is a Holy Well dedicated to S. Cadvan. We were told that the waters are "troubled" at certain hours of the day, and patients bething there were sure to be cured. The well looked very black and cold, but several rheumatic people were there, waiting for the proper moment to bathe, and fully believing in its efficacy. |

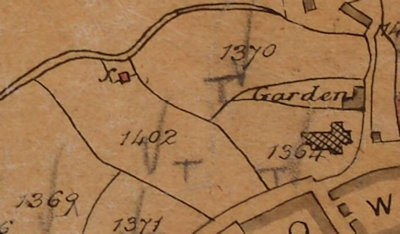

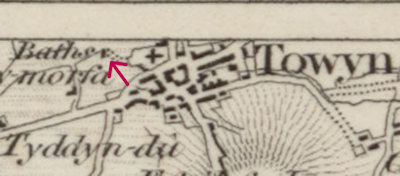

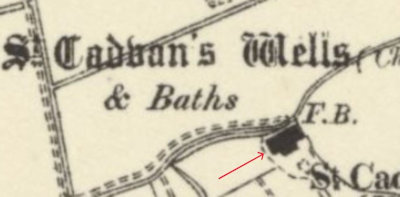

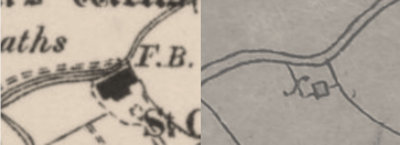

After studying several old maps, I personally think that two different bath-houses have been built on the site. A square building set in a small enclosure is shown on a tithe map from 1841 and, despite its looks, it appears that this was a bath house, as an Ordnance Survey map of 1834, which subsequently predates the tithe map, shows a similar small building to the west of the church, labelled as "Baths". This structure that is shown in the tithe map certainly is the well, a fact that is proven by the name of the field in which the structure is located: "Well Meadow". However, by the 1880s, the shape of the building has changed from a square to the present T-shape; from this point onwards, the building is named as "St Cadvan's Wells", in the Gothic script.

|

|

|

|

As no Ordnance Survey maps were produced of the area between 1834 and 1887, it is impossible to tell exactly when the bath house was either re-built or improved and extended. The idea, however, of the well being at one time a square construction of some kind is supported by what is written in Black's Picturesque Guide to North Wales, which was first published in 1855:

|

Contiguous to the west side of the church is a large square well, called St. Cadfan's Well, formerly supposed to be efficacious in cutaneous and rheumatic diseases. |

It is therefore certain that the present T-shaped bath-house replaced the smaller square one at some point between the years of 1855 and 1887.

There is some confusion over when exactly the well was destroyed and converted into what it is now. Francis Jones, in The Holy Wells of Wales (1954), stated that "In 1894, the owners of the baths, finding they did not pay, filled them in with stones and converted the buildings into a coach-house and stables." However, it is doubtful that this date is correct, as the well is still marked on Ordnance Survey maps well into the early 20th century, and the bathing facilities are mentioned in several tourist guides that were published after that date, which not only suggests that St Cadfan's Wells still existed for many years after 1894, but also implies that the site was still a major tourist destination, and therefore would certainly have generated income. One such reference to the well can be found in Cassell's Gazetteer of Great Britain and Ireland, which was published in 1900:

|

During the summer months T. is frequented by numerous visitors, and, in addition to the facilities for bathing, numbers are attracted by the fame of St. Cadfan's Well, noted for the cure of rheumatic disorders. |

The well is also mentioned in John George Bartholomew's The Survey Gazetteer of the British Isles, which was published in 1904, and states that "St. Cadfan's Well is resorted to by rheumatic patients". The well and baths are marked as extant on an Ordnance Survey map of 1953; this map was revised in 1948 and so it appears - if the map is correct - that the well must have been destroyed at some point between the years of 1948 and 1954 (the date of Francis Jones' book The Holy Wells of Wales). I also find it doubtful that the baths were converted into a coach-house and stables after this time, as the building is simply not large enough to have ever been a coach-house, with attached stables. Possibly a coach-house and stables was constructed nearby to house the visitors to the well, maybe during the Victorian era, although Jones is likely right when he says that the wells were filled in when they ceased to yield any profit. After both World Wars, tourism to Tywyn decreased massively, and it is probably this that caused the decline of the baths. Alternatively, the well may have dried up when the surrounding fields were drained, and this would certainly have forced the bath-house to close. Instead of becoming a coach-house, Ordnance Survey maps suggest that the baths, once they had been destroyed, became part of a "Builder's Yard".

Today the building that was once the baths still exists, although it looks like it has been converted into a residential property. The main fabric of the building, however, has not changed (at least not on the outside) since its construction. The main image on this page shows the building as it appears today. The spring that once supplied the well probably drains into one of the many drainage ditches that exist in the fields to the north of the bath-house, if it did not run dry when the fields were drained, that is. Coflein records that the "outline of baths can reportedly be detected" inside the building.

Images:

Old OS maps are reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

Copyright 2025 britishholywells.co.uk