|

Dedication: Saint Barrwg Location: Barry Island Coordinates: 51.39001N, -3.26614W Grid reference: ST119664 Status: dry/capped Heritage designation: none |

|

Dedication: Saint Barrwg Location: Barry Island Coordinates: 51.39001N, -3.26614W Grid reference: ST119664 Status: dry/capped Heritage designation: none |

St Barrwg, also variously called "Barruc" and "Baruch", was a 6th century disciple of the famed St Cadoc. According to the Life of St Cadoc, recounted by the Rev. W. J. Rees in Lives of the Cambro British Saints (1853), Barrwg sailed to Barry Island one day with Cadoc and another of his disciples, Gwalches. Upon their arrival, Cadoc is said to have asked his followers what they had done with his "Enchiridion" (this being his "manual book"), which both Barrwg and Gwalches had reputedly left behind, in their forgetfulness. Quick to anger, Cadoc commanded them to sail back and retrieve the book, apparently saying "Go, and never return!"; he watched their journey from the comfort of Barry Island. Unfortunately for Barrwg and Gwalches, Cadoc's word was fulfilled, and it is said that, on the return journey with the book, the boat suddenly capsized and both of them drowned. This did not considerably inconvenience Cadoc, however, as the Enchiridion later turned up in the bowels of a large salmon that he was about to consume. The legend goes on to note that Barrwg's body washed up on the shore of Barry Island, and was thus buried there.

Whether there is any truth in this story is questionable, but there definitely was a saint named Barrwg active in the area at some point in the 6th century, and the fact that the centre of his medieval cult was clearly focused on Barry Island suggests that he actually was buried there, even if he had not drowned in the vicinity, as the medieval Life of St Cadoc attests. In fact, Barrwg is reputed to have founded at least two medieval churches in the area, notably those at Barry and at Penmark. It is surely no coincidence that Penmark is located incredibly close to Llancarfan, the site of St Cadoc's famous clas, which establishes a possible authentic link between the two saints.

It is not clear how quickly Barrwg's cult developed on Barry Island after his death, but, by the late medieval period, a chapel had been constructed over the supposed site of his grave, and it had become, along with the holy well, a popular place of pilgrimage; of course, both the chapel and the well had probably been on the island since at least the 7th century, if not earlier. Regardless of the site's age, however, the earliest reference that I have found to a tradition of pilgrimage to the island appears in John Leland's Itinerary, written just after, and in some parts during, the Reformation. Leland did not mention the holy well, and instead focused on the chapel, which he described as "a fair litle Chapel of S. Barrok, wher much Pilgrimage was usid". Although Leland's description implies that all pilgrimage to Barry Island had already ceased by the time of his writing, pilgrims were still visiting the holy well (if not the chapel) in the early 19th century, the custom clearly having been revived at some point before the late 17th century, assuming that it ever ceased at all.

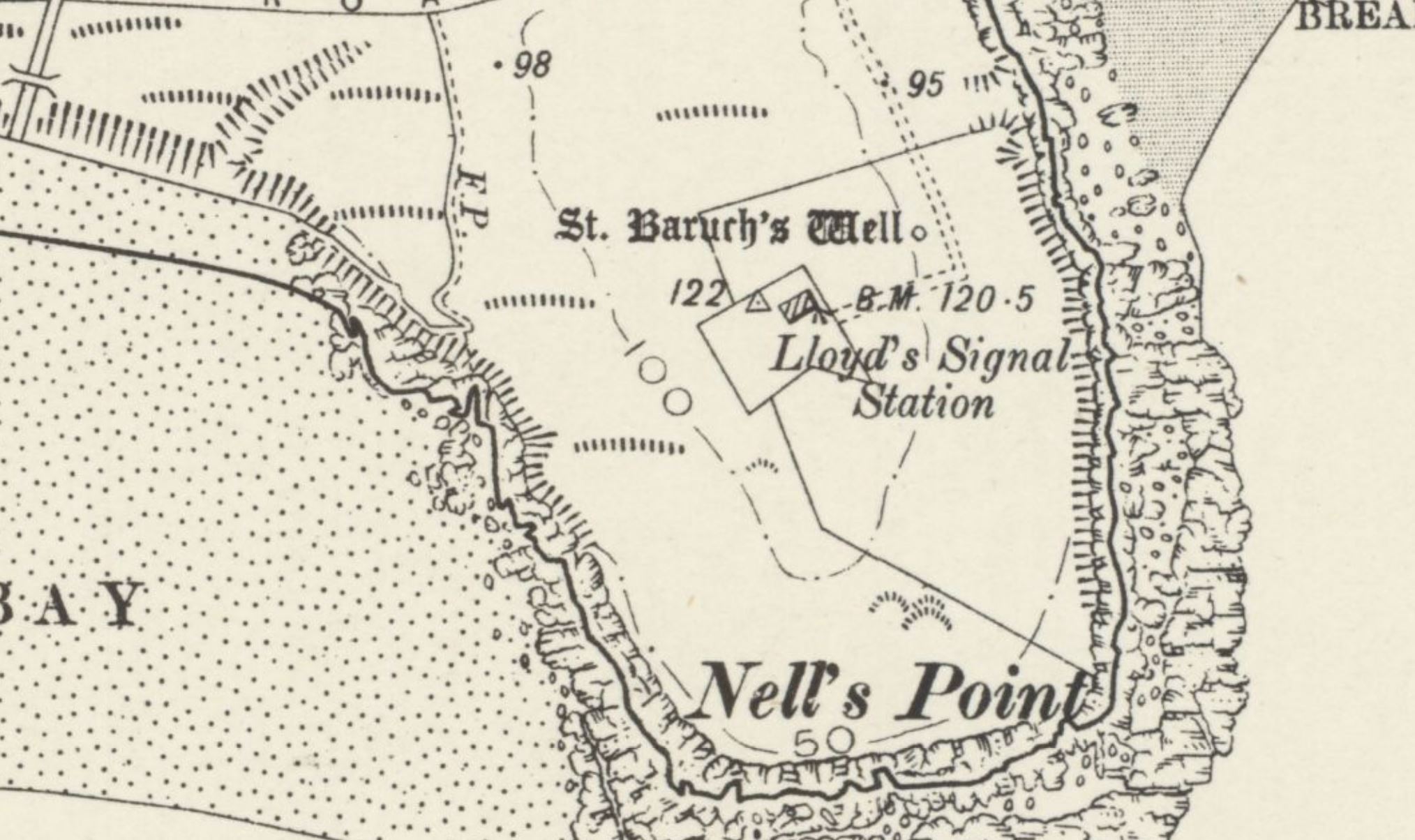

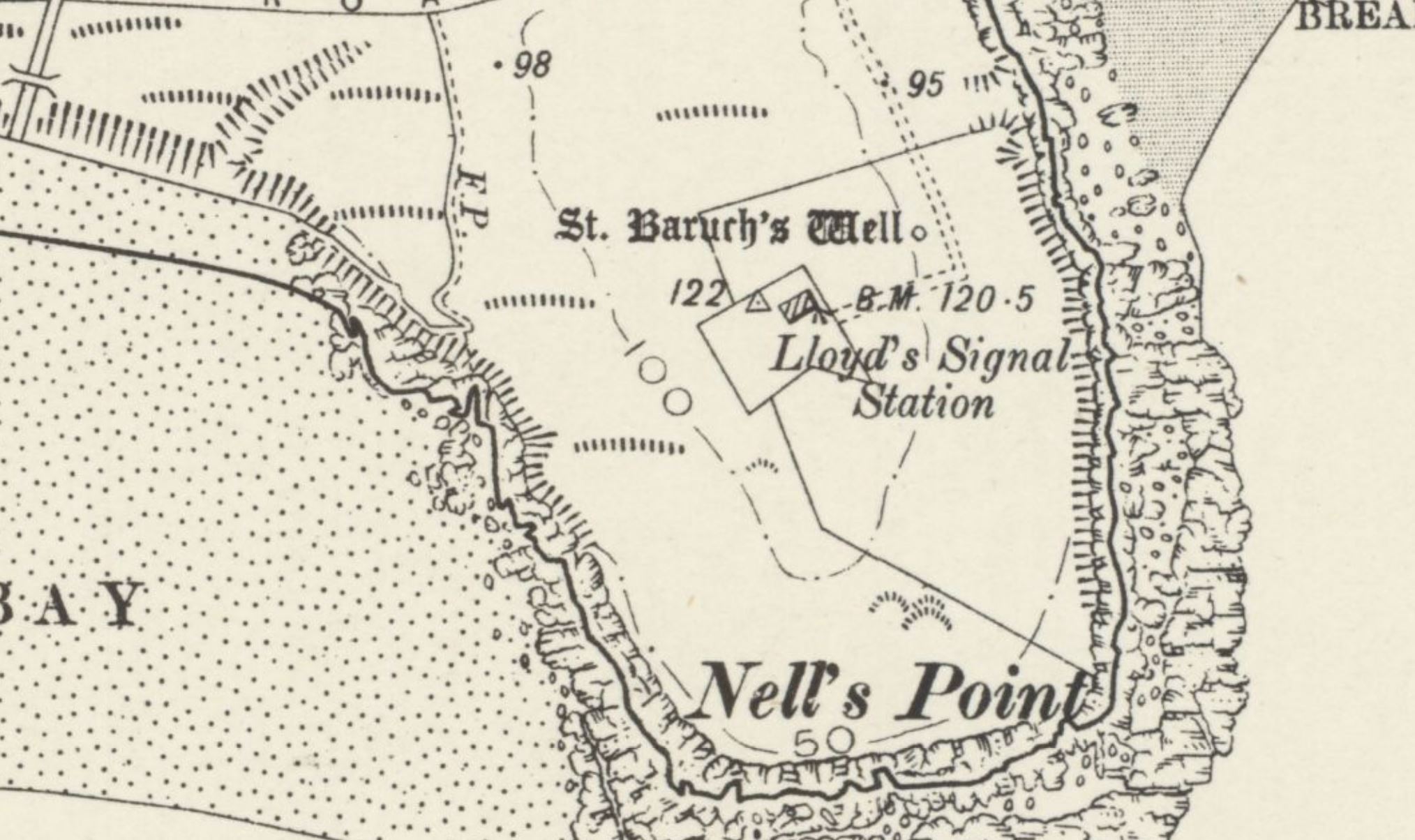

In fact, the earliest mention that I have found to the well itself dates from the close of the 17th century, and appears in Edward Lhuyd's Parochialia, in which an unnamed spring "on ye S.E part" of the island, "within an 100 or 100 & 20 yds of ye cliff side", that was clearly Ffynnon Faruch, is mentioned in correspondence from a Mr David Spencer, regarding Barry Island. Spencer described it as "a well of very good watter", effective in the curing of "ye K[ing]'s evill", "feavers", "agues", "paine in ye Head", and "sore eyes". Undoubtedly, these were remnants of a medieval custom associated with the well, and probably also involving the chapel, that had survived.

However, by the early 19th century, the majority of this tradition had been either abandoned or forgotten, and the well's supposed curative powers had become limited only to sore eyes. According to Dudley Fosbrooke, writing in 1817 in British Monachism, "great numbers of women" were still in the habit of travelling to the well "on Holy Thursday", where, after washing their eyes in the spring, "they drop a pin" into the water. Wirt Sikes claimed in British Goblins (1880) that a local inkeeper once found "a pint" of pins in the well whilst cleaning it out.

Sikes also reported that the tradition of visiting the well on Holy Thursday had abruptly stopped after the landowner, Lord Windsor, closed the island to visitors in the May of 1879, wishing to convert the island "into a rabbit warren". However, Yr Haul, a Welsh magazine, published an article in 1879 entitled Ffynnonau Cyssegredig a Hen Ddefodau ("Sacred Wells and Ancient Rituals") that claimed the well had been "gorchuddio gan y tywod" ("covered by sand"), an alternative explanation for the recent cessation of the custom. Although it is not immediately clear which of these explanations were true, or whether both may be accurate, it is definite that the Holy Thursday tradition was discontinued at around this time, and did not experience a revival. The well seems to have been almost completely abandoned after this point.

Unsurprisingly, Ffynnon Faruch is little mentioned after 1900. Apart from the fact that it was still marked on Ordnance Survey maps, I have found only a few sources from this time that register its existence. The 20th century did not fare well for the spring, as it was destroyed in 1966, during the construction of a new holiday park on Barry Island; the supply of water from the well was probably used in the camp. This holiday park was later demolished, however, and a housing estate constructed on its site, with a commemorative monument erected on the exact site of Ffynnon Faruch that can still be seen today.

|

Access: The monument on the site of the well is publicly accessible. |

Images:

Old OS maps are reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

Copyright 2025 britishholywells.co.uk