|

Dedication: Saint Germanus Location: Moel Smytho Coordinates: 53.09572N, -4.20338W* Grid reference: SH525576* Status: covered Heritage designation: none |

HOME - WALES - CAERNARFONSHIRE

|

Dedication: Saint Germanus Location: Moel Smytho Coordinates: 53.09572N, -4.20338W* Grid reference: SH525576* Status: covered Heritage designation: none |

St Germanus of Auxerre, a Gaulish bishop who journeyed across Britain during the early 5th century, undoubtedly founded the church of Betws Garmon at some point during his travels. He was first sent to Britain in 429 by Pope Celestine I, with the primary purpose of stamping out any traces of Pelagianism, a controversial new doctrine that opposed the concept of original sin, and which had been designated as heresy by the Pope. At the time, the doctrine was gaining popularity in Britain, which is no surprise, given the fact that Pelagius, its founder, was British himself. Germanus appears to have had considerable success in convincing the Celts to abandon Pelagius' teachings, and although only fragmentary parts of his cult survived the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons in England, his cult in North Wales, one of the oldest in the country, remained strong throughout the medieval period.

Despite the fact that there is no certain evidence that Germanus, or Garmon, as he became known in Wales, ever used Ffynnon Armon himself, it is highly likely that he would have baptised new converts in the spring, as Christianity was still very new to the region in the early 5th century, and he was one of its earliest proponents in Wales. There is also a chance, given its remote hillside location, that the holy well was originally worshipped by the local inhabitants in a pagan context, before it was converted into a Christian holy site by St Garmon.

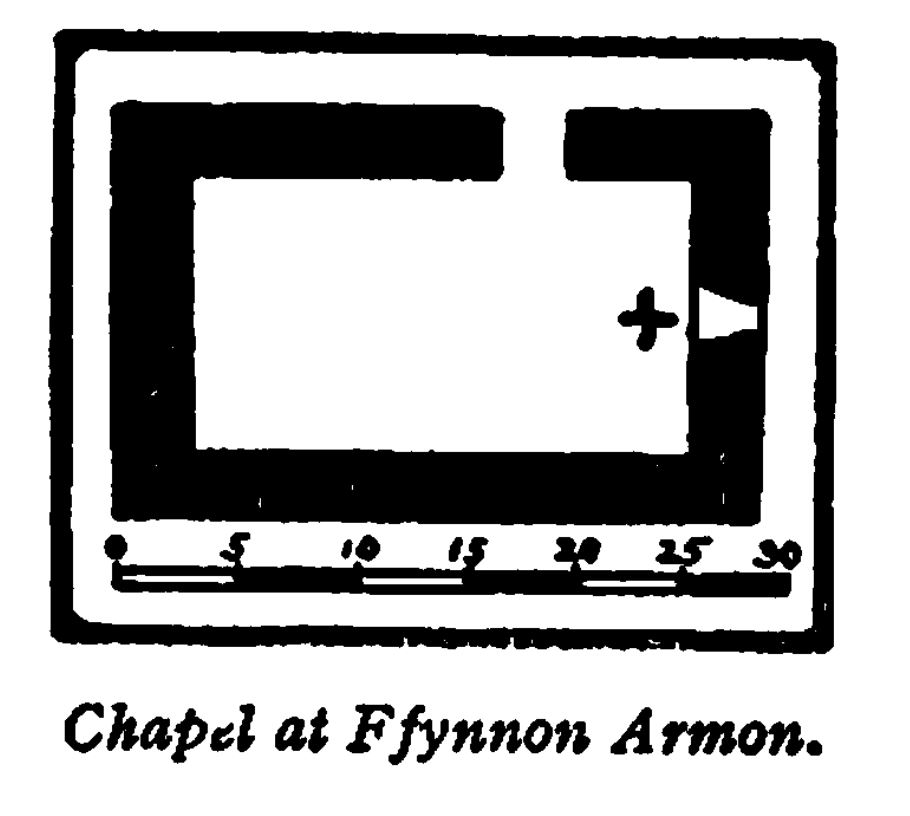

Irrespective of its origins, Ffynnon Armon had almost certainly become a place of regular pilgrimage by the late medieval period. Intriguingly, there is strong evidence to suggest that a rectangular stone construction, situated around 90 metres below Ffynnon Armon on the hillside, and labelled on historic Ordnance Survey maps as a "Sheepfold", may once have been a medieval well-chapel. The earliest mention that I have found of this idea dates from 1924, and appears in Old Churches of Snowdonia, by H. Harold Hughes and Herbert L. North. Hughes and North described it as "the remains of a small structure", measuring internally "23 ft. in length" and "12 ft. 6 in. in width". They also reported on the existence, in the east wall, of a "rudely constructed light", with a width and height of "1 ft. 6 in." and "1 ft. 7 in.", respectively, and attested that an opening on the north side of building was "doorway". A plan of the construction was published alongside this description:

|

The Royal Commission's description of the site, dating from the mid 20th century, is more detailed than that published in Old Churches of Snowdonia, and further suggests that this construction was a medieval chapel of some description. It is worth noting that the site was placed within the category of "secular buildings" in the Commission's Inventory of monuments in Caernarfonshire, so the inspecting officer evidently did not feel certain that the remains were those of a religious landmark. Their report was as follows:

|

Building near Ffynnon Garmon, 23 ft. E.-W. by 12 ft. 6 ins., on a levelled platform at ca. 750 ft. above O.D., in a slope facing E. The walls, ca. 3 ft. thick, are well built, of large blocks with pinnings. There is a small square window in the centre of the E. end, and a door on the N. 7 ft. 6 ins. from the N.E. corner; on its E. side a slab about 1 ft. 6 ins. square projects externally at ca. 3 ft. above ground level. At the E. end, and for part of the N. side, the wall stands on a rough plinth. The S. wall seems to have been partly rebuilt. |

The fact that the foundations are built upon a "rough plinth", presumably to accommodate the steep gradient of the hillside, strongly suggests that this was not built as a "Sheepfold", as early Ordnance Survey maps claim. So does the existence of the small projecting "stone slab", which, being positioned against the east wall, was almost certainly once a medieval altar; it is also important to note that the whole building is aligned east-to-west, which is typical of medieval churches and chapels. There can be, therefore, little doubt that this construction, tentatively dated by Hughes and North to the "early sixteenth-century", was a medieval chapel linked to Ffynnon Armon. Given its situation in regards to both the spring and the parish church, it seems probable that the three sites would have been connected by a path or track leading up the hill, and terminating at the well; pilgrims may have paused at the chapel to deposit offerings to the saint, or to take a rest, which would have been welcomed especially by the sick or injured.

Indeed, the fact that the well was, until at least the early 19th century, still believed to possess a range of curative powers indicates that Ffynnon Armon would, in medieval times, have been used primarily for healing purposes. The earliest reference that I have found to this usage of the spring (and, in fact, the earliest reference that I have found to the spring itself), dates from 1828, and appears in the second volume of William Cathrall's History of North Wales, under the heading of "Bettws [sic] Garmon". According to Cathrall, who described Ffynnon Armon (or, as he called it, "St. Garmon's Well") as "a fine spring of water" located on a hillside roughly "a mile west of the church", the well "is reputed to be efficacious" in the curing of both "rheumatic complaints and eruptive disorders".

Whether this tradition survived past the 1820s is uncertain, although, as a number of late 19th century gazetteers and topographical guides mention the well in conjunction with healing, it is probable that the site was still used for healing purposes for several more decades, perhaps even until the close of the 19th century. Of course, there is a high chance that the authors of these guides were only copying Cathrall's original remarks, as was common at that time, so these later books may not be accurate at all. Either way, the tradition seems to have died out by the early 20th century, when Myrddin Fardd, writing in 1908 in Llên Gwerin Sir Gaernarfon, attested that the spring had previously been used for the cure of "clafr, crydcymalau, iddwf, pob rhyw grugdarddiad yn y croen, &c." ("scabies, rheumatism, itch, all kinds of crusting in the skin, &c."), but indicated that the custom had been abandoned.

Regarding Ffynnon Armon's medieval structure, assuming that it had one, and that its water was not just piped directly to the chapel (although this is unlikely, something similar probably happened at Ffynnon Dderfel, in Merioneth, also located on a hill; pilgrims here do not seem to have visited the spring itself, but appear to have accessed the water at the foot of the slope in some kind of bath), nothing is recorded. If pilgrims did access the water at Ffynnon Armon itself, and not at the chapel, then it is likely that the spring would have been housed in some kind of stone structure, perhaps similar to those still extant at Ffynnon Gelynin and nearby Ffynnon Beris: a square or rectangular pool surrounded by stone seats (this style of housing seems to have been very popular in Caernarfonshire during the medieval period). All appears to be lost, or at least covered in dense undergrowth, today.

The earliest description that I have come across of the site's appearance can be found in Old Churches of Snowdonia (1924), in which the spring is, rather vaguely, said to be housed within a "rude intake formed to supply water to the dwellings" at the foot of the hill; the Royal Commission corroborated this statement with the claim that Ffynnon Armon had been "bricked round to form a farm water supply". Intriguingly, the Historic Environment Record (which is certainly not a trustworthy source, so may be inaccurate in this instance) asserts, apparently drawing upon the report of OS surveyors from 1973, that the spring had been "bricked around and covered with slate", and that the possible remains of a "stone step" had been seen "on the N side"; it is not clear whether this refers to the north side of the concrete trough (pictured above), or to the site of the spring.

When I visited Ffynnon Armon myself in August 2025, I used GPS, in conjunction with my map, to ascertain that I was looking in the correct location. The entire area was covered with dense undergrowth, and, at the original location of the spring, which is shown on both historic and, curiously, modern Ordnance Survey maps, I could see no trace of either a structure or any water. However, it is worth noting that the original site of Ffynnon Armon was buried beneath a very large quantity of moss, branches, and plants, beneath which there almost certainly will be some sort of structure, if only a receptacle for water. Nevertheless, there was something left of Ffynnon Armon still to see: around ten metres to the east, at SH5257957660, I found a large, square basin built of concrete blocks (bearing the hallmarks of an early 20th century construction), which housed a sizeable plastic tank, into which water could be heard trickling. The plastic tank was capped off by a thick slab of slate, and was connected to three pipes: a small, blue pipe that led down the hillside and seemed to come out of the hill some twenty or so metres to the east in the form of a large, black plastic tube, which itself became the source of a small stream; a larger, white pipe from Wickes that presumably led to the houses at the foot of the slope; and another pipe that could be seen leading to it from the original site of the well. The square basin itself was evidently damp, but not wet, and was surrounded by a wire fence.

This concrete construction is evidently the "rude intake" described in Old Churches of Snowdonia, although the Royal Commission's statement could refer to either this, or to something buried beneath the moss at the original site of the spring. It is worth noting that the Coflein database inaccurately describes the well as "a natural spring trickling out of an embankment", and specifically states that there is no structure, or any remains of one, in the vicinity; in all likelihood, this describes part of the stream lower down the hillside, which, in some places, does look a lot like a spring emerging from the ground.

On my visit to the site, I was unable to reach the remains of the chapel, due to the dense undergrowth covering the hillside. It is also important to note that the main image on this page is of the concrete structure, not of the site of the spring (pictured below).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Access: According to modern Ordnance Survey maps, a public footpath should run directly past the well. When I visited the site, I found that the main footpath leading up the hillside did not even vaguely resemble that shown on the OS map, but it did eventually lead past the site of the spring, and the concrete enclosure. |

*This is the original location of the spring, not of the concrete structure

Images:

Google Maps data ©2025 Imagery ©2025 Airbus, Bluesky, Infoterra Ltd & COWI A/S, CNES / Airbus, Maxar Technologies

Copyright 2025 britishholywells.co.uk