|

Dedication: Saint Withburga Location: East Dereham Coordinates: 52.68102N, 0.93735W Grid reference: TF986133 Heritage designation: Grade II listed building |

|

Dedication: Saint Withburga Location: East Dereham Coordinates: 52.68102N, 0.93735W Grid reference: TF986133 Heritage designation: Grade II listed building |

The 7th and early 8th century St Withburga, a (probable) daughter of King Anna of East Anglia, and, therefore, the sister of the famed St Aethelthryth of Ely, had a direct link to Dereham and a convent in the town. It is not clear when exactly this convent was founded, or even who exactly was its founder: some sources state that King Anna himself founded it in 650, and made Withburga its prioress; according to others, Withburga only became a nun after her father's death, which probably occured in 654; Leland, however, asserted that Withburga herself founded the convent, but that she only did so after Aethelthryth had founded Ely in 673. Today, it is popularly accepted that it was Withburga who founded East Dereham's convent, although this really cannot be proven for certain.

Withburga is said to have died in 743, after which she was buried in the churchyard of East Dereham. According to legend, roughly fifty years after her initial burial, her coffin was opened and her body was found to be completely incorrupt. Following this discovery, and perhaps because of it (although, more probably, because St Withburga's cult was gaining some popularity locally), Withburga's remains were translated to a shrine within the church. It seems logical that it was at this time that the spring became associated with St Withburga, likely on the part of the locals, who hoped that it would attract pilgrims. Indeed, earlier forms of the legend of the well's creation assert that it was as a result of Withburga's first translation that the spring sprung up, supposedly on the site of her churchyard tomb; this is definitely the authentic medieval legend (by the 18th century, several different forms of the legend were circulating). However, Withburga's body was soon to be uncovered again, and this time by the monks of Ely, who, already possessing the bodies of St Aethelthryth and her sisters St Sexburga and St Ermenild (all of whom were Withburga's sisters), and perhaps wishing to complete the family collection, travelled to East Dereham in 974 with a cunning plan to steal Withburga's remains. The monks of Ely, upon their arrival in East Dereham, held a large feast for the entire town; once the villagers were suitably drunk, the monks crept into the church and removed the body of St Withburga from her coffin, which, it is said, they found to be completely intact. The monks then took the supposedly incorrupt body and carried it across the fens to Ely Cathedral, where Withburga was placed in a new tomb, along with the bodies of her three sisters. A note that is said to have been left on the altar of East Dereham's church by the Abbot of Ely after he stole the relics of Withburga was included in the church guide in the late 1800s, and mentioned in a letter published in Notes and Queries in 1865:

|

I, Abbot of Ely, and Lord of Dereham, by and with the consent and approval of Edgar the King, have translated the body of St. Withburga to be hereafter kept in Ely Abbey with increased splendour and reverence; and This, Presbyter of Dereham, is my Receipt for the blessed Body aforesaid. |

Withburga's body was supposedly discovered intact yet again in 1106, when the bodies of the four sisters were translated into a new tomb within Ely Abbey. Thomas, a monk of Ely who claimed to have witnessed the event first-hand, described the state of the bodies in 1107; this account was published by Alban Butler in Lives of the Primitive Fathers, Martyrs, and Other Principal Saints (1757):

|

The bodies of SS. Sexburga and Ermenilda were reduced to duſt, except the bones. That of St. Audry was entire, and that of St. Withburge was not only ſound, but also freſh, and the limbs perfectly flexible. Warner, a monk of Weſtminster, shewed this to all the people, by lifting up, and moving ſeveral ways the hands, arms, and feet. Herbert, biſhop of Thetford, who, in 1094, tranſlated his ſee to Norwich, and many other perſons of diſinction, were eye-witneſſes hereof. |

Although the relics of St Withburga had been taken from East Dereham, the saint's cult still prospered locally, and it seems that the holy well was a site of pilgrimage in the medieval period. The earliest mention of St Withburga's Well that I have been able to find is rather unusual in the fact that it actually predates (only by a few decades) the Reformation. At this time, there was a chapel located directly over the spring, which managed, surprisingly, to survive the Reformation, before it was taken down in 1565. This early reference was made by John Capgrave in 1516 in a publication entitled Nova Legenda Anglie, in a section that retells the story of Withburga's life:

|

Tranſlatu eſt autem eius venerabile corpus in ecclesiam quam ipſa viuens ibidem construxerat. De loco autem quo prius ſepulta fuerat, fons aque lucidiſſime emanat, multis diuerſarum beneficia conferens ſanitatum. Translation: Her [Withburga's] venerable body was then transferred to the church which she had built there whilst she was alive. From the place where she had been buried before, a spring of very clear water flows forth, conferring many diverse health benefits. |

In 1691, Henry Wharton echoed exactly Capgrave's remarks, in volume 1 of Anglia Sacra, indicating that little had changed since 1516. It was little mentioned in the 17th century, so it may have fallen out of favour as a result of the Reformtion; however, the well regained some fame in the 18th century. The site was already famous by the 1740s, at least according to Thomas Tanner, writing in 1744 in Notitia Monastica, who described it as "a famous well", and noted that it had "corruptly" become known as "St. Winifred's". It was in 1752 that the well was "arched over, and converted into a cold bath" (so said Francis Blomefield in 1775).

The cold bath was certainly popular, as it was expanded in 1793 and a brick building was constructed over it that completely covered the spring, for, according to John Chambers, in volume 2 of A General History of the County of Norfolk (1829), the "public benefit". It was still standing when Chambers was writing, and he described it in detail:

|

The building is situated at the distance of about four yards from the west door of the church, and the spring, which rises under the ruins of the tomb, is very pellucid, and the water very fine; but, from its entire concealment from the sun, by the building erected over it, is considered too cold for any person to bathe in it whose constitution is not very robust. It is open to the public, and many persons bathe in it during the summer season, and such is the force of habit, that a respectable inhabitant of the town, who died at an advanced age, used this bath daily winter and summer. |

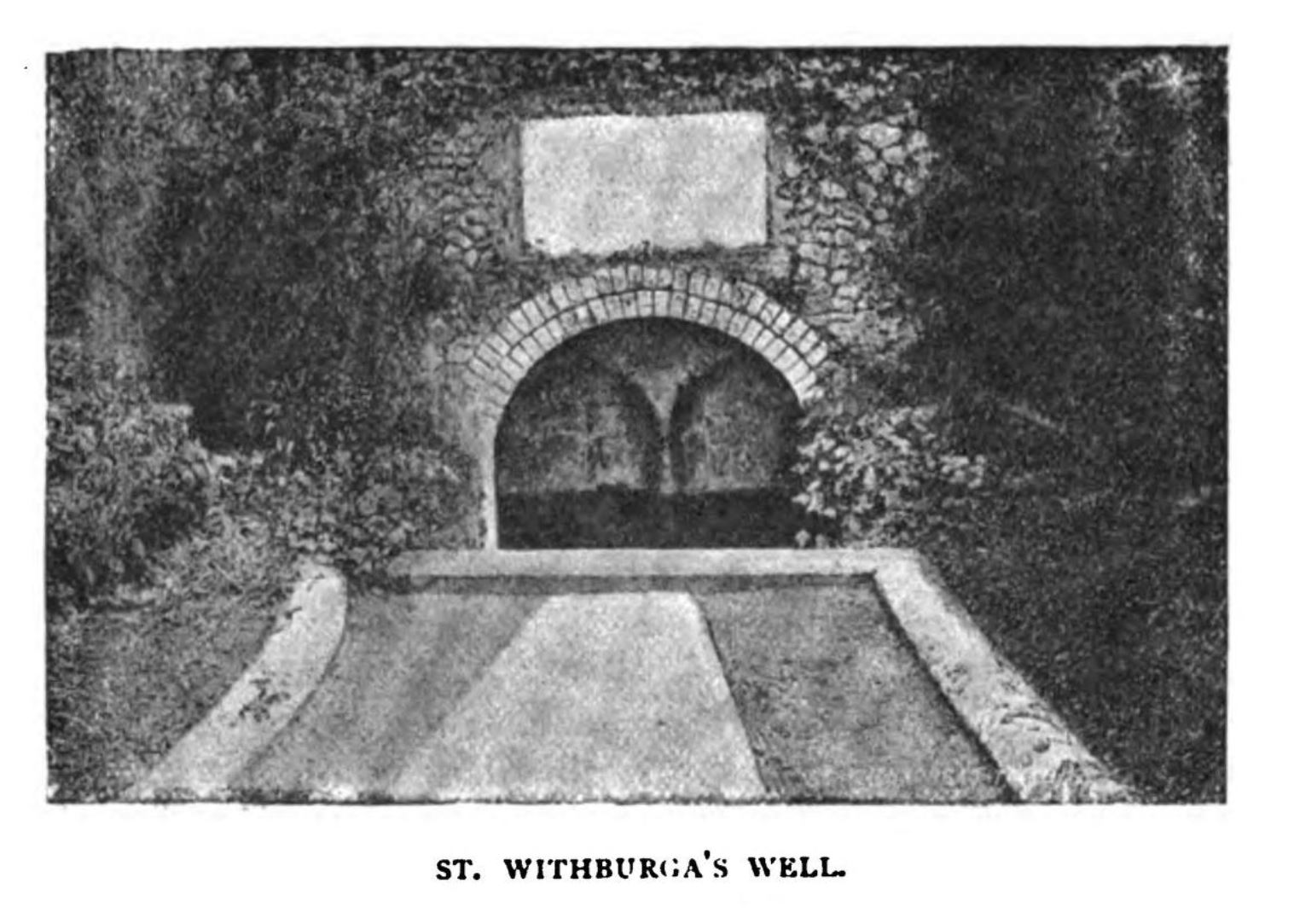

This bath-house was also described by a Mr W. Sparrow Simpson in a letter to Notes and Queries that was written in 1852 as "a rude building"; he stated that the inscription that can now be seen on the wall above the spring was, in his time, located on the building's "western front". Possibly because the almost cult-like obsession with cold bathing that had gripped England in the previous century was beginning to pass, this building was demolished soon after Simpson's visit. Although I have been unable to find an exact date for the demolition, R. C. Hope, writing in 1893 in The Legendary Lore of the Holy Wells of England, stated that it had occured twenty-five years prior. He also published a photograph of the site, which shows how little it has changed in the last century or so.

|

In 1885, it was commented in The Saturday Review that St Withburga's Well looked "slimy and uninviting". When I visited the site in the February of 2025, the well was not exactly "slimy", but the water did look slightly stagnant. The 18th bath itself still exists, despite the fact that the bath-house is long gone, and the site was in very good condition.

|

Access: The well is located in the churchyard, which is open to the public. |

Copyright 2025 britishholywells.co.uk