|

Dedication: Saint Gofor Location: Kensington Gardens Coordinates: 51.5035N, -0.18441W Grid reference: TQ261798 Heritage designation: none |

|

Dedication: Saint Gofor Location: Kensington Gardens Coordinates: 51.5035N, -0.18441W Grid reference: TQ261798 Heritage designation: none |

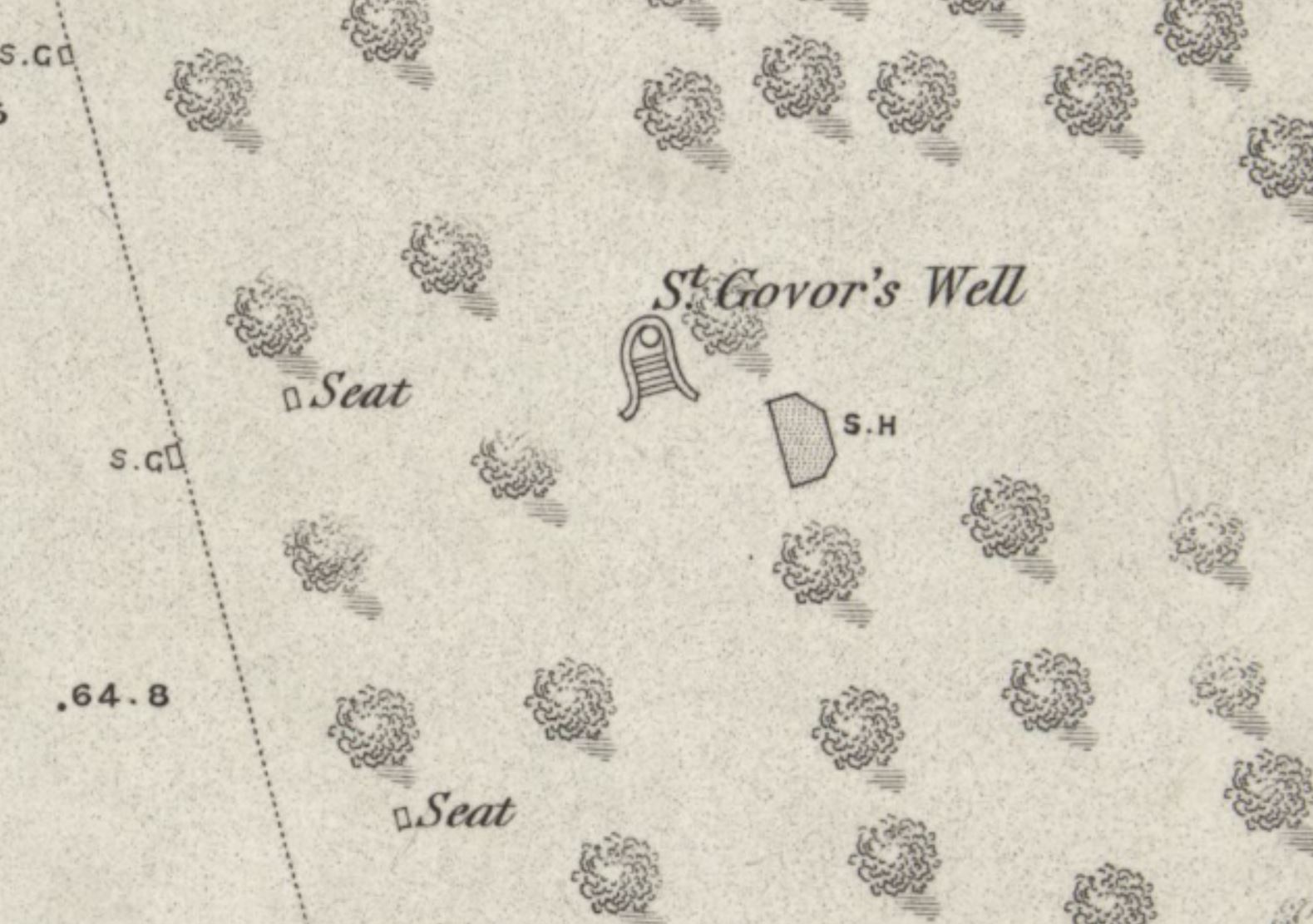

St Gofor, a minor 6th century Welsh saint from Monmouthshire, never travelled to London, and his very localised medieval cult certainly did not have a presence in Kensington. In fact, St Govor's Well was built in 1856 by Sir Benjamin Hall, who, as the First Commissioner of Works, wanted to improve London's public parks, including Kensington Gardens. He was also the Baron of Llanover, and it appears to have been for this reason that Hall chose Gofor as the patron of his newly constructed drinking fountain. Although the inscription on the current drinking fountain claims that it was originally fed by a spring, the 1851 Ordnance Survey plan of London (which was incredibly detailed) shows absolutely nothing on its site, suggesting that Hall built it completely from scratch.

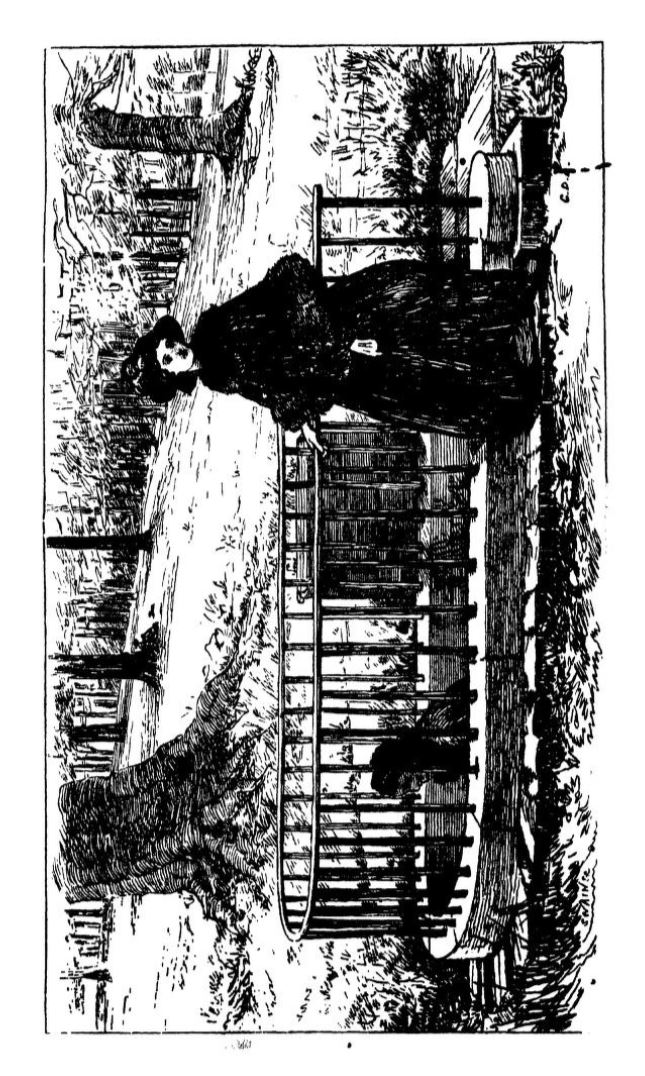

Soon after its construction, St Govor's Well quickly became a well-known feature of the park, and its waters gained such a good reputation that the Commission of Woods and Forests appointed an elderly lady to sit beside the spout, and sell the water to wayfarers in, according to a piece in the British Medical Journal published in November, 1886, "many coloured glasses". Quite interestingly, the drinking fountain also soon gained a reputation for possessing healing powers (particularly for "crippled limbs"), despite the fact that it was a completely new holy well and was nothing more than a folly. In the September of 1856, shortly after the site was built, the Punch magazine published a satirical poem about the well, mentioning the elderly lady, and making a mockery of both the water's supposed curative properties, and of Benjamin Hall himself:

|

'Mid the royal glades of Kensington, six green-clad keepers walk, Last year the youngest flirt of the clan dissolved into skin and bone, One summer morn, 'neath the chesnut [sic] shade as he pensively strolled about, At its shrine for months, with a mug in his hand, he was wont on his knees to fall, That spirited Welshman covered the well, and made it a sacred spot, She details to the crowd this right ancient fact, but still there's a fact more quaint, Then success to the good St. Gover's Well, we no more shall at Bath be bled, |

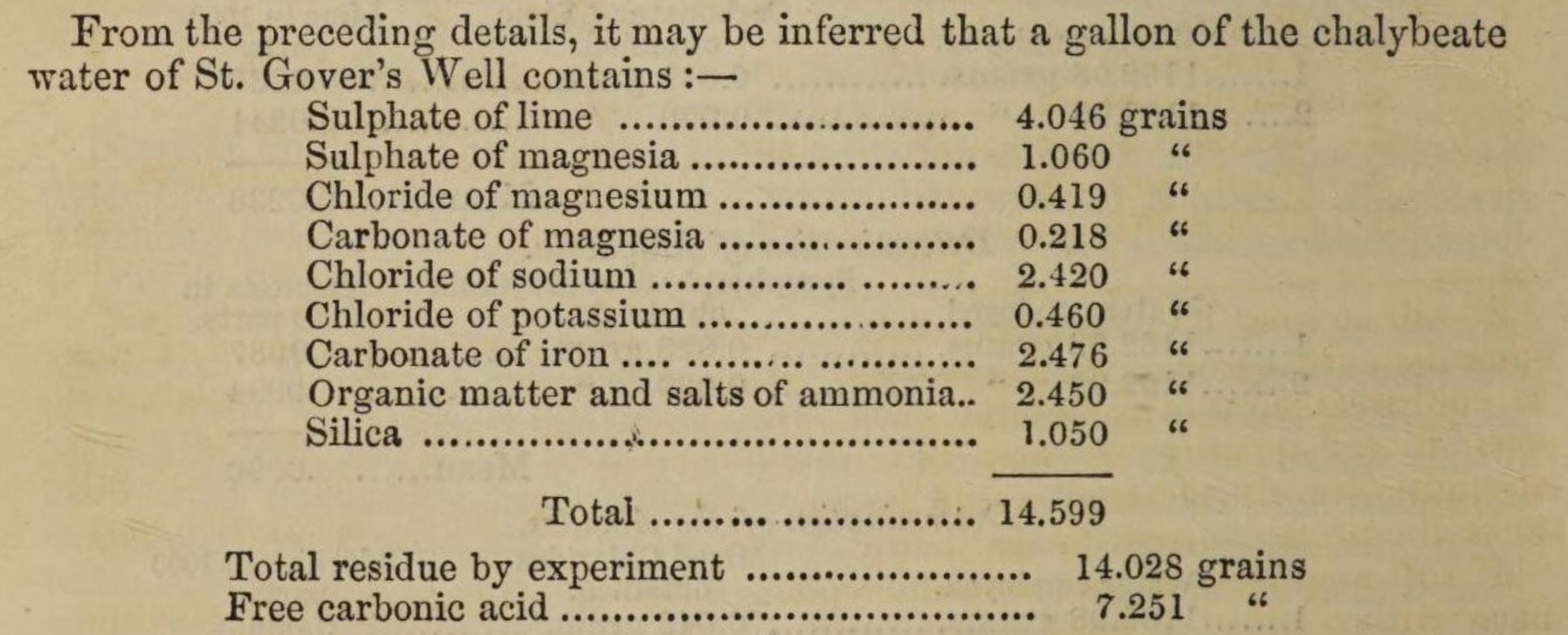

Only two years after the drinking fountain had been built, a Mr J. B. Barnes decided to produce an analysis of the water. He attested that the spring had been "discovered about three years ago by some workmen engaged in draining between the pond and the trees on the south side", although whether it really was fed by a spring is debatable. His analysis, which was published in The Pharmaceutical Journal in 1858/9, was not particularly damning, unlike later attempts at ascertaining the water's contents:

|

However, several years later, an analysis of five of London's "well known sources" of water, carried out in 1875 by a Mr Wanklyn, found that the water of St Govor's Well was less than pure. The Sanitary Record noted on the 30th of October, 1875, that the drinking fountain "scarcely deserves" its "special reputation", as it was found to be "loaded with organic matter", containing "above 0.10 of albuminoid ammonia". On the 1st of November, 1875, a local newspaper reported that the "inhabitants of the old Court suburb have been rather shocked this week" at the results of the analysis, and that the well would probably "be closed". Nonetheless, people continued to drink the water, in the hope of improving their health, and W. Caret Hazlitt, in a piece in the Antiquary, published in 1886, entitled Notes on our Popular Antiquities, related that the fountain was "still visited by persons who have faith in the virtues of the water". However, the British Medical Journal, in 1886, detailed an event that indicated that St Govor's Well was perhaps not fed by a spring at all:

|

During the past summer, while the Round Pond has been drained St. Govor's Well has run dry, and it is said that some pipes were discovered under the two or three feet of stinking mud at the bottom of the pond which had the appearance of communicating directly with the well, so that it seems probable that the water has been filtered through the mud, and not through the intervening bed of gravel. Can its reputed medicinal virtues be due to the organic impurities of stagnant water? It is hoped that the source of the water will be fully investigated, and, if it is found to be the mere drainage of the pond, that the well will be closed, or else that a supply of pure water will be laid on from a known source. The well would be very much missed by the children, as there is no other drinking-fountain in the gardens. |

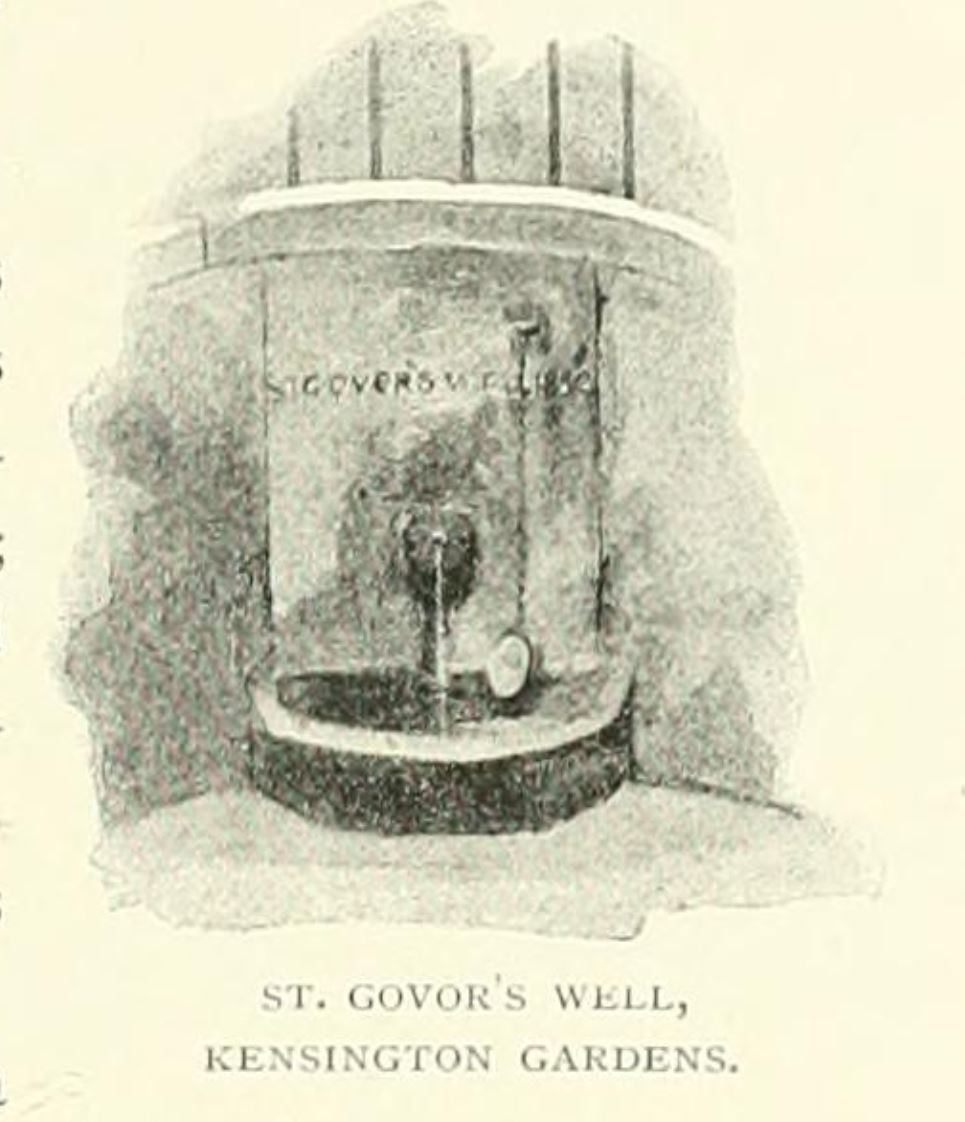

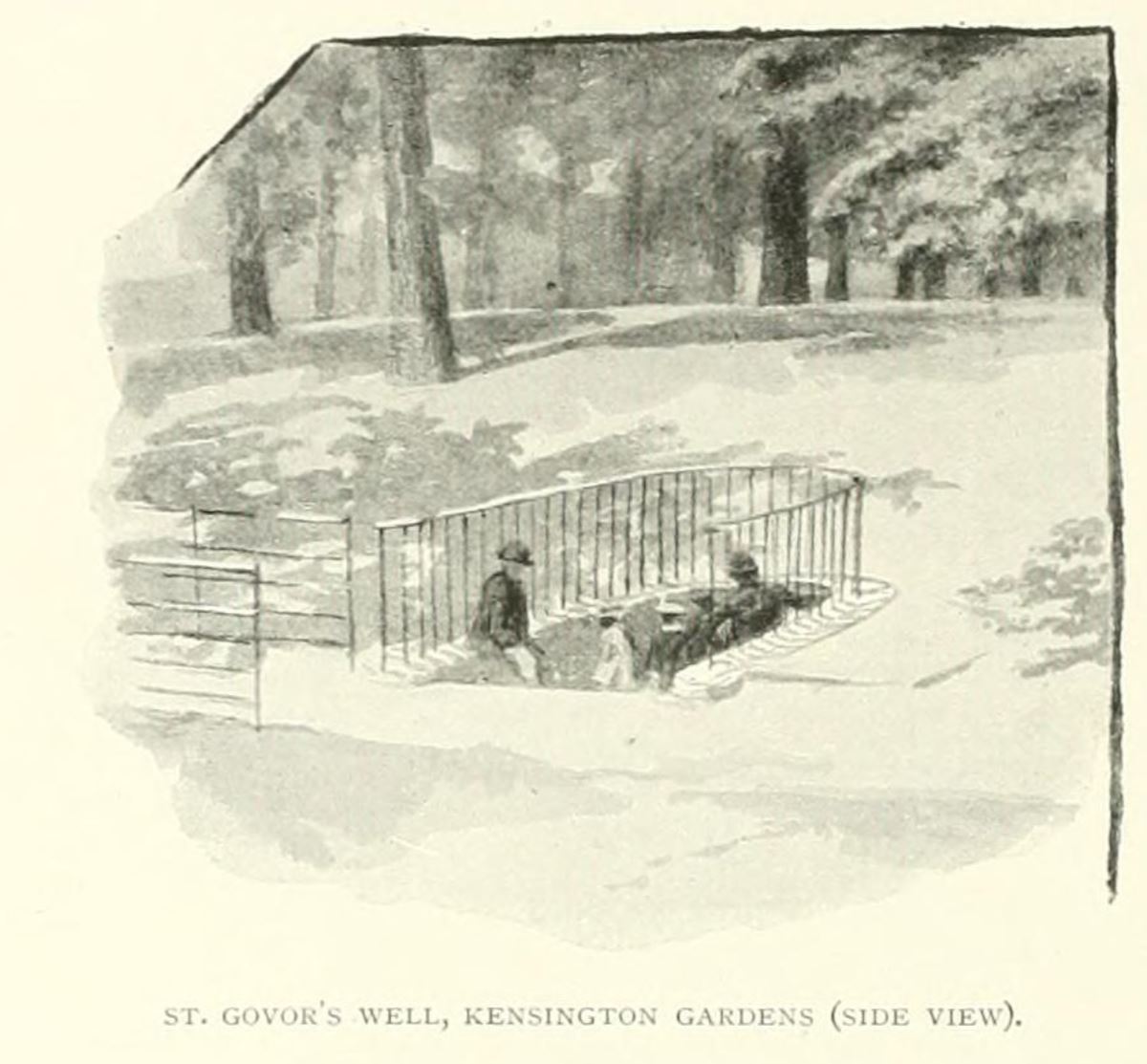

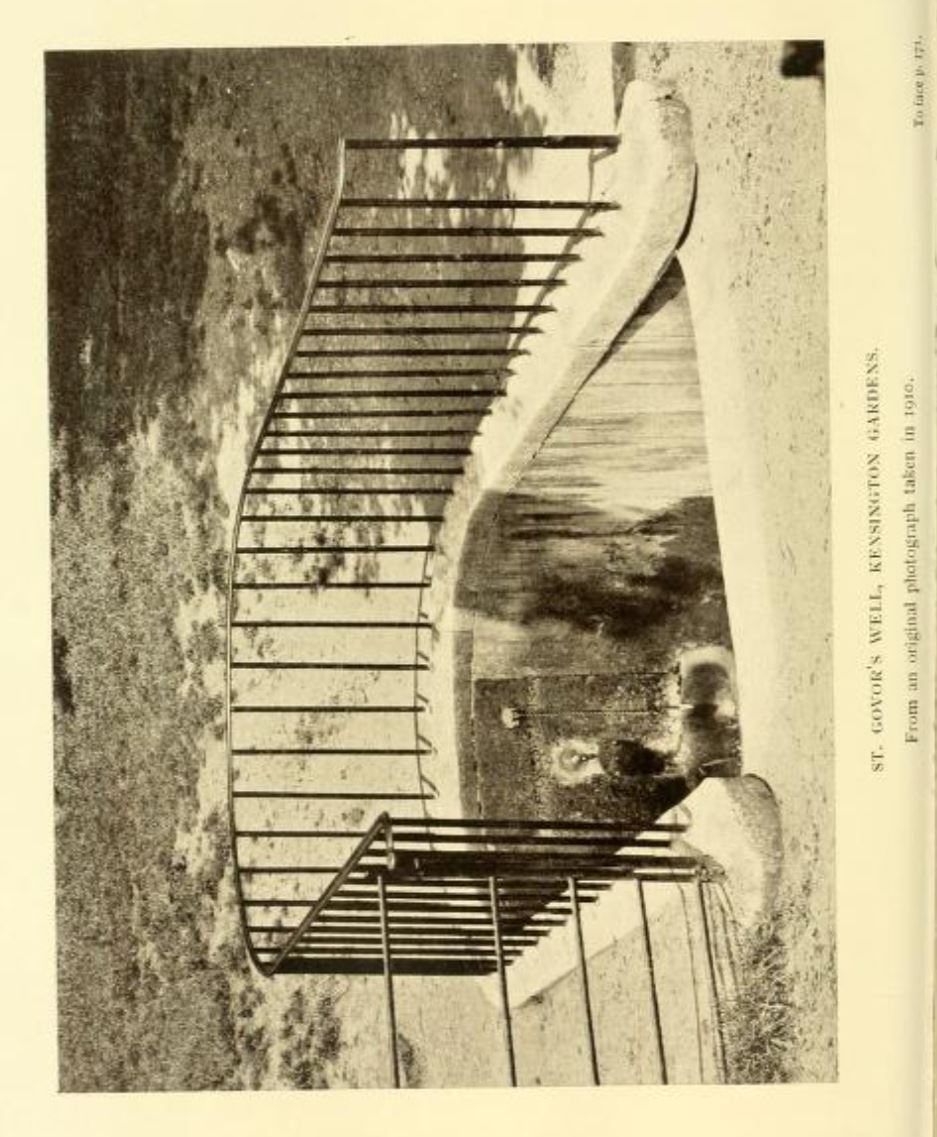

This discovery seems to have caused a rapid decline in the drinking fountain's popularity, and The Lancet reported in February, 1897, that "the saint has deserted the shrine", and "the water, it is to be feared, has lost its healing efficacy". The Victorian drinking fountain itself remained unchanged until very recently, when it was replaced with the unusual circular structure that exists today. The original fountain built by Sir Benjamin Hall consisted of a leaden spout, in a small sunken enclosure, reached by several stone steps. "St Govor's Well, 1856" was reputedly inscribed on the structure. It was surrounded by iron railings, and waste water issued into a stone basin beneath the spout. Perhaps the only alteration that was ever made to the structure before it was demolished was the installment of a metal cup, for the use of nursery maids and children, which appeared at the fountain after the elderly lady resigned from her post. Luckily, a considerable number of illustrations, and even one rare photograph, of the Victorian structure exist:

|

|

|

|

|

When I visited the site in the May of 2025, the current drinking fountain was working (presumably the water is now taken from a cleaner source) and it appeared to be in good condition.

|

Access: Kensington Gardens are open to the public daily, free of charge. |

Images:

Old OS maps are reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

Copyright 2025 britishholywells.co.uk