|

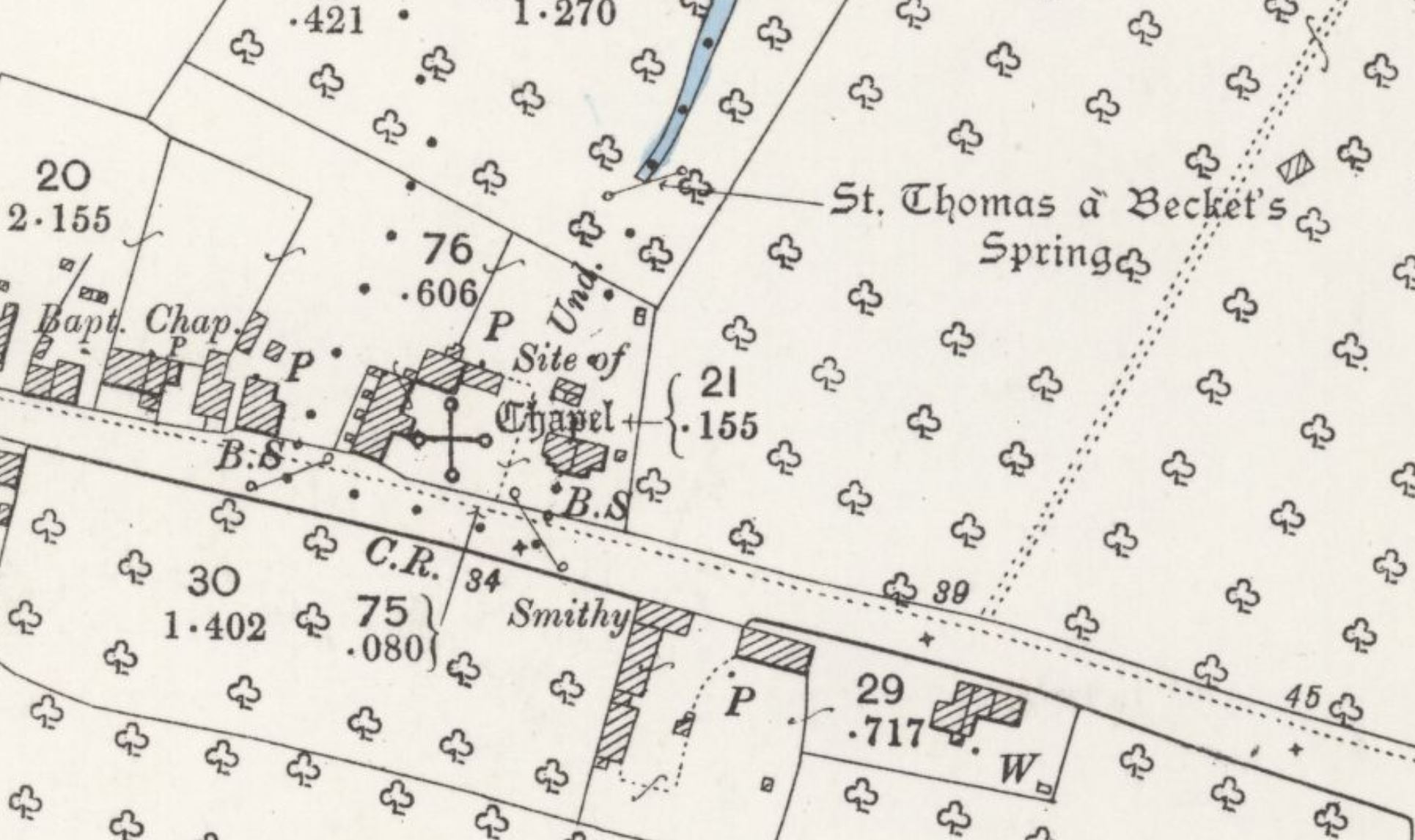

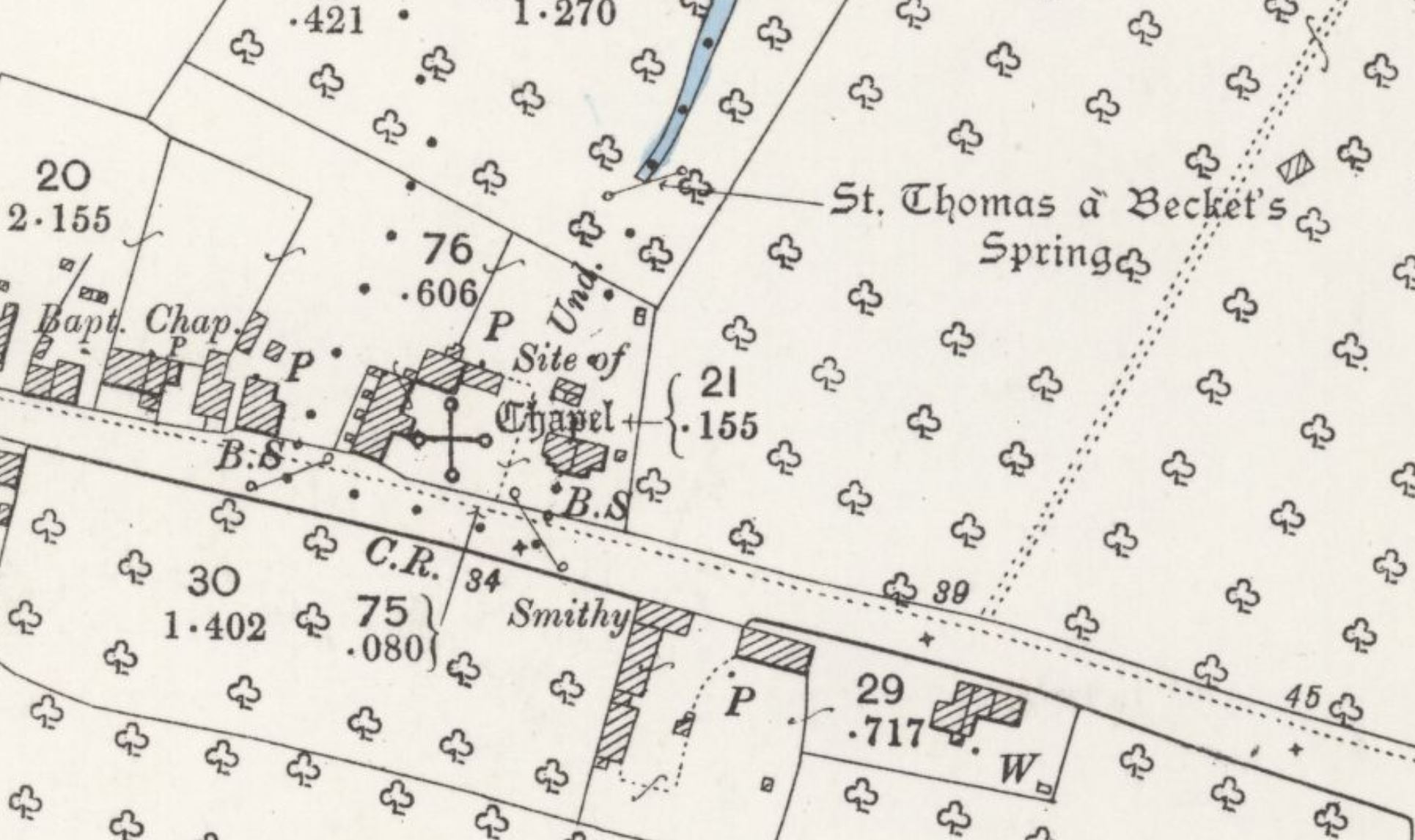

Dedication: Saint Thomas Becket Location: Tong (parish) Coordinates: 51.33478N, 0.77042W Grid reference: TQ930631 Heritage designation: none |

|

Dedication: Saint Thomas Becket Location: Tong (parish) Coordinates: 51.33478N, 0.77042W Grid reference: TQ930631 Heritage designation: none |

Although St Thomas' Well later became one of the landmarks for pilgrims on their way from London to Canterbury, there is a possibility that it may have borne an earlier significance. In or around the year 679, a religious synod or council was held by, according to the 1776 Kentish Traveller's Companion, "Archbiſhop Brightwald" of Canterbury, at a place recorded as "Baccancelde". Edmund McClure, writing in a letter sent to The Athenaeum on the 25th of December, 1897, attested that the name is a compound of the "Jutish kaelda", meaning "well", and the word "Baccan", which McClure believed was the "genitive case" of the name "Bacca, [or] Backe"; apparently this was a "well-known N. Friesic personal name". If this is the case, then "Baccancelde" must mean "Bacca's Well", perhaps referring to a spring owned by a person named "Bacca". Indeed, although it is impossible to say for certain that this place-name relates to Bapchild, there is strong evidence to suggest that it does: the later forms "Baeccacild" and "Bachanchilde" were listed by Isaac Taylor in the second edition of Names and Their Histories (1898), and McClure himself recorded the "intermediate form" of "Bacchild" from 1685. These examples suggest very strongly that the name "Bapchild" is derived from "Bacca's Well", which would almost certainly have been the most important well in the parish: the one later known as "St Thomas Becket's".

Assuming that this is the case, then the name of the site must have been subtly changed from "Bacca's" to "Becket's" by someone very enterprising, at some point after Watling Street began to be used as a pilgrimage route to Canterbury. This would likely have occurred at some point during the late 12th, or early 13th, century, after which time Canterbury became a major destination for pilgrims. The site certainly also had some facilities for pilgrims, whether in the form of a well-chapel or, as some sources suggest, a religious hospital, which may have been constructed when Bacca's Well became Becket's Well.

Unfortunately, however, very little is known for certain regarding the facilities attached to the well site, apart from the fact that something existed there for the convenience of pilgrims. One of the earliest references that I have found to this building dates from 1782, when Edward Hasted wrote in the second volume of The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent that "part of the walls of an oratory", located "on the north ſide" of the "high road" (this being Watling Street) could still be seen. Hasted recorded a local theory regarding its purpose: he stated that "ſome" believed it had been "erected in memory of the celebration of this council" of 697, and later "made uſe of by the pilgrims" to Canterbury, who he claimed "offered up their prayers for the ſucceſs of their pilgrimage" at the Bapchild "oratory". Whilst it seems quite unlikely that a chapel built in 697 would survive, serving no apparent purpose, until the time of Thomas Becket, the fact that it was evidently locally remembered to have been used by pilgrims, as well as its situation, suggests that it was linked to St Thomas' Well. Also intriguing is the fact that only remnants of it remained, suggesting that it had been partially destroyed, perhaps during the Reformation.

There is, however, another theory to explain the existence of the construction. Whilst the idea that Hasted recorded simply suggests that it was some kind of pilgrim chapel, something not uncommon along pilgrimage routes like that from London to Canterbury, Canon Scott-Robertson, a late 19th century antiquary, had a different theory. Scott-Robertson believed that Hasted's "oratory" was actually the remnants of the "Lepers' Hospital of St. James of Puckleshall", accompanied by its "chapel and cemetery". A medieval hospital of this name, although not necessarily for lepers, was included in William Dugdale's Monasticon Anglicanum, "in the parish of Tong". Dugdale wrote that, as Scott-Robertson attested, it was "dedicated to St. James", and was "granted by King Henry the Seventh to Linch his physician" (by "Linch", Dugdale must have meant Thomas Linacre). This certainly suggests that Puckleshall Hospital had a medical focus, although its dedication to St James, patron saint of pilgrimage, was noted as being unusual for a leper hospital by Edward Hutton in England of My Heart: Spring (1914).

Indeed, although its patronage establishes a potential link between the hospital and the holy well, there is absolutely no certainty as to the location of Puckleshall Hospital within the parish of Tong, so there is a chance that it was situated somewhere else within the parish. Of course, as both St Thomas' Well and the chapel or hospital site are located just within the bounds of Tong, it is possible that the hospital of St James of Puckleshall really was associated with the holy well: perhaps the existing hospital began to accommodate pilgrims to Canterbury, and converted Bacca's Well to Becket's for that very purpose. Almost certainly the most convincing piece of evidence, however, is the fact that Puckleshall hospital is, according to Canon Scott-Robertson, known to have possessed a "cemetery", and Henry Littlehales, writing in 1898 in Some Notes on the Road from London to Canterbury in the Middle Ages, reported that "persons now living" had seen "bones disinterred when it has been necessary to disturb the soil" at the site of Hasted's "oratory". As a simple pilgrim chapel would not have had a graveyard like this, St Thomas' Well almost certainly was linked to the Hospital of Puckleshall, which would explain its dedication to St James.

Despite the fact that parts of the hospital's walls were in existence in the late 18th century, a fact confirmed by the statement in The Kentish Traveller's Companion (1776) that "a ſtone wall about ſixty feet long" could be seen "on the north ſide of the road", they had been demolished by the early decades of the 1800s, at least according to J. H Brady, writing in The Dover Road Sketch Book (1837), who admitted that he "could trace no vestige" of it when he looked "in 1836". This was corroborated by Henry Littlehales in his aforementioned 1898 Notes on the Road from London to Canterbury, in which he described a visit to the site that was conducted in 1897:

|

Now, 1897, we find on the north side of the road at the east end of the village a red brick wall enclosing a yard. Immediately west of this yard is a red brick barn-like structure, and west of this is a stile and little rough footpath. The footpath will take us through a garden, at the end of which we can step over a rough fence into an orchard where almost immediately at our right is a little hollow containing St. Thomas's Well, now known as Spring Head. |

By the last years of the 19th century, St Thomas' Well does not appear to have possessed any structure, or, at least, nothing of any particular notability. The same seems to have been the case in 1893, when a description of the well was published in a document entitled the Appendice to Minutes of Evidence taken before the Royal Commission on Metropolitan Water Supply. This document records that "St. Thomas-a-Becket's Spring" is found "in a rather deep hollow N. of the high road", but makes no mention of its structural appearance. Possibly the most telling is the report of OS surveyors in 1963, who described the site as "a nettle-filled hollow from which a series of springs issue".

Unfortunately, I have not been able to find any information relating to the well's structural appearance at all, and anything that did exist there in medieval times would likely have been destroyed during, or shortly after, the Reformation. In fact, I have not come across any references to any of the site's traditions, although it must have had at least one legend associated with it, to explain its convenient existence at the side of the pilgrims' route.

Even when I visited Bapchild myself in August 2025, I was unable to glean much more information about the well's history, and it was clear that its name is no longer, as the OS surveyors attested it was in 1963, "known locally". In fact, I was even unable to access the holy well itself, due to the heavy extent to which the banks of the stream that issues from it were overgrown. Nevertheless, I spoke to the tenant of the adjoining paddock, who was not aware of the spring's name or history, but informed me that the water rose in a deep hollow into which many trees had fallen, and that it would only be accessible "with a chainsaw". Intriguingly, however, she also said that in the floor of the neighbouring house's garage, during building work to convert it into an extension, an old well had been found. This apparently occurred some years ago, and I found that the owner of the relevant property had only recently moved in, so was unaware of the discovery.

What makes the existence of this old well so interesting is the fact that it was located directly on the site of the hospital or pilgrim chapel. Because of its proximity to St Thomas' Well, a clearly very copious water source, there would have been no need, at least in terms of a water supply, for a deep well of this kind to ever have been dug here, and yet it must have been linked to the hospital or chapel. It seems highly likely that the well may have been part of a medieval system to transport the water from the spring, located in an unaccessible hollow some distance from the pilgrim road, to the chapel, where pilgrims or a priest could easily collect the holy water. The fact that this deep well had evidently been covered over by the late 19th century, according to OS maps, which mark nothing at the location, suggests that it had no practical purpose, and was possibly even filled in after the Reformation.

|

Access: At the moment, the well is unfortunately impossible to reach from any angle, because it is so completely overwhelmed with fallen trees and undergrowth. |

Images:

Old OS maps are reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

Copyright 2025 britishholywells.co.uk