|

Dedication: Saint Ann Location: Buxton Coordinates: 53.25863N, -1.91464W Grid reference: SK057735 Heritage designation: Grade II listed building |

HOME - ENGLAND - DERBYSHIRE

|

Dedication: Saint Ann Location: Buxton Coordinates: 53.25863N, -1.91464W Grid reference: SK057735 Heritage designation: Grade II listed building |

The Roman settlement that occupied the site of modern Buxton was known as "Aquae Arnemetiae", "Arnemetiae" being Arnemetia, a Romano-British goddess to whom St Ann's Well was originally dedicated. Aquae Arnemetiae is thought to have housed the major shrine of this deity, which most probably centred around the well and Roman baths. Intriguingly, Aquae Arnemetiae was linked to a nearby settlement now called Brough, which also possesses a holy well of St Ann, by a Roman road called "Bathom gate"; this indicates the presence of a localised cult of Arnemetia in this part of Derbyshire.

Until 1709, the remains of a stone wall that was undoubtedly part of the Roman shrine or bathing complex could be seen surrounding St Ann's Well. Charles Leigh, writing in 1700 in The Natural History of Lancashire, Cheshire, and the Peak, asserted that this wall was "cemented with red Roman Plaiſter" that was "hard as Brick", and that "appears as if burnt". He theorised that the substance was made of a "Mixture of Lime and powder'd Tiles cemented with Blood and Eggs". Additionally, the remains of a Roman lead cistern, fed by water from the now lost St Peter's Well, were discovered in around 1695 when (according to Thomas Short, in his Natural, Experimental, and Medicinal History of the Mineral Waters of 1734) workmen were "driving up a Level to the Bath". This cistern was reportedly located "fifty Yards Eaſt" of St Ann's Well, and consisted of "Sheets of Lead ſpread upon great Beams of Timber, about four Yards Square, with broken Ledges round about".

Of course, Arnemetia's shrine was soon Christianised, and it is no surprise that a saint with a similar name was chosen to take her place. The new shrine of St Ann appears to have become, at least by the late medieval period, quite elaborate. There seems to have been a small-scale medieval bathing complex at the site, at least by the early 16th century. There can also be no doubt that a medieval chapel of St Ann was located on the site, perhaps constructed directly over the well: the Valor Ecclesiasticus, created by Thomas Cromwell in 1535, on the orders of Henry VIII, mentions, in relation to "Capella de Bukstones in parochia de Bakwell" ("the chapel of Buxton in the parish of Bakewell"), "oblationibus ibidem ad Sanctum Annan" ("offerings there to St Ann"). Indeed, the foundations, according to Thomas Short's History of the Mineral Waters, of this chapel were uncovered in around 1695 (at the same time as the leaden cistern), and a "large Piece of its Wall" was dug up. This chapel was probably destroyed either during the Reformation or shortly afterwards.

The earliest known reference to the existence of St Ann's Well dates from around the 1460s, and appears in the Itinerary of William of Worcester, who mentioned "Halywell principium aque de Wye in comitatu Derby per centum vltra London facit plura miracula faciendo jnfirmos sanos et in hieme est calida velut lac mulsum", meaning "Halywell, the source of the Derbyshire River Wye a hundred miles from London, performs many marvels in curing the sick, and in winter it is as warm as new milk". Although he did not mention the site's association with St Ann, the well almost certainly was dedicated to her by this date.

In 1536, St Ann's Well and the associated chapel and baths were visited by Sir William Bassett, one of Thomas Cromwell's commissioners, who removed the image of St Ann of Buxton from the site and locked up the bathing facilities, on the orders of Cromwell himself. A transcript of the original letter that Bassett sent to Cromwell after his visit was published by Thomas Wright in 1843, in Three Chapters of Letters Relating to the Suppression of Monasteries:

|

Ryght honorabull my inesspeyciall gud lord, acordyng to my bownden dewte and the teynor of yowre lordschypys lettres lately to me dyrectyd, I have sende unto yowre gud lordschyp by thys beyrer, my brother, Francis Bassett, the ymages off sentt Anne off Buxtone and sentt Mudwen of Burtun apon Trentt, the wych ymages I dyd take frome the place where they dyd stande, and browght them to my owne howss within xlviije. howres after the contemplacion of yowre seyd lordschypis lettres, in as soober maner as my lyttull and rude wytt wollde serve me. And ffor that there schullde no more idollatre and supersticion be there usyd, I dyd nott only deface the tabernaculles and placis where they dyd stande, butt allso dyd take away cruchys, schertes, and schetes, with wax offeryd, being thynges thatt dyd alure and intyse the yngnorantt pepull to the seyd offeryng; allso gryffyng the kepers of bothe placis admonicion and charge thatt no more offeryng schulld be made in those placis tyll the kynges plesure and yowre lordschypis be ffurther knowen in that behallf. My lord, I have allso lokkyd upp and sealyd the bathys and welles at Buxtons, thatt non schall enter to wasche them, tyll yowre plesure, and I schall nott fayle to execute yowre lordschipis cummandmentt to the uttermust of my lyttul wytt and power. And, my lord, as concernyng the opynion off the pepull and the ffonde trust that they dyd putt in those ymages, and the vanyte of the thynges, thys beyrer my brother can telle yowre lordschype much better att large then I can wryte, for he was with me att the doing of all, and in all placis, as knowyth Jhesu, whome ever have yowre gud lordschyp in hys blessyd kepyng. Wrytten att Langley, with the rewde and sympyll hande of yowre assuryd and feythfull orator, and as on ever att yowre cummandmentt next unto the kyng to the uttermost of my lyttull power. William Bassett, knyght. |

Despite Cromwell's efforts, the baths had been re-opened by, at the very earliest, 1569, when William Cecil (also known as Lord Burghley) wrote to the Earl of Shrewsbury in the August of that year, regarding the fact that the Earl had been "earnestly advised of yor phisicians to goo thether for the recovery of yor helth". Indeed, only a few years later, in 1572, the physician John Jones published the first treatise on the Buxton waters, entitled The Benefit of the Auncient Bathes of Buckstones. He listed a multitude of diseases that the water had the power to cure, including "Rheumes", "Feuers", "Headaches", "Weak ſinewes", "Old ſcabbes", "Ulcers", "Crampes", "Numnes", "Itchinges", "Shrinkings", and "Ryngwormes", and mentioned "the bayne inuencions about S. Anne found in the well", which he reckoned not "worthy the recitall". He noted that the baths had been "brauely beutified with ſeats round about", so that patients were "defended from the ambyent ayre", and could "ayre your garmintes in the Bathes ſyde". Interestingly, Jones attributed the healing powers of the water not to its mineral properties, as most other physicians of his day would have done, but to God (in fact, he did not even publish an analysis of the water), and he finished his treatise with a copy of "the Prayer uſually to be ſayd before Bathing". He also suggested to his readers that they enter "the day of your cōming thither", and "the day of your departure, with the country of your habitation, condition or calling, with the infirmityes, or cauſe you came for, in the regyſter booke kept of the warden of the Bath, or the Phiſition that ther ſhalbe appointed, & the benefite you receyued, paying foure pence for the recording". This record book was kept in the Old Hall, adjacent to the well, until 1670, when it was unfortunately destroyed during the house's reconstruction.

Mary Queen of Scots famously visited Buxton on several occasions, to use the well and bathing facilities. The 6th Earl of Shrewsbury, George Talbot, who was appointed Mary's keeper, already owned the Old Hall in Buxton (which he had built himself, at some point before 1572); perhaps it is for this reason that Mary chose to go to Buxton, instead of travelling to other holy wells elsewhere. Talbot first took Mary to Buxton in 1573, although both he and Queen Elizabeth appear to have been reluctant to comply with Mary's wishes. On the 15th of July, 1573, Talbot wrote to Sir Francis Walsingham to request the Queen's permission for him to take Mary to Buxton, relating that Mary "hath charged me... that hyr goyng thedr is referred to me, and I am therby hindrr of hyr health by stopinge hyr frome thens", and that she "complayns more of hyr hardnes in hyr syde then of late". He received a response from the aforementioned Lord Burghley on the 10th of August, who informed Talbot that the Queen had consented, although she "was very unwyllyng" to do so. This first trip to Buxton does not appear to have gone completely to plan, and Talbot later described the events in a letter written to Lord Burghley in 1580:

|

My very good L. ...& touching the doubtfullnes her Mate shuld have of me, in gyvyng the Scotes Q. lybarté to be sene, & saluted; suerly, my L. the reportars thereof to her Mate hathe done me grete wronge: In dede, at her fyrst beinge there, ther hapenyd a pore lame crepell to be in the lowar [missing word] unknowne to all my pepell that garded the plase; & whan she hard that ther was women in the [missing word], she desiered some good gentylwoman to gyve her a smoke; wherupon they putt one of ther smokes out of a hole in the walle to her: & so soone as it came to my knolege, I was bothe offended wt her, & my pepell for takeyng any lettars unto her; &, aftar that tyme, I toke such ordar as no pore pepell cam unto the house during that tyme; nether, at the seconde tyme, was ther any strangar at Buxtons (butt my one pepell) that sawe her, for that I gave such charge, to the contrey about, none should come in to behold her. |

Mary visited Buxton at least five times, her final journey there being in the June of 1582, when, apparently knowing that this would be her last visit to the well, she etched a farewell on her window in the Old Hall, which read, according to William Camden, writing in 1590, "Buxtona quæ calidæ celebrabere nomine lymphæ, / Forte mihi poſt hac non adeunda, vale" (the English translation of Camden's work, published in 1610, provided a translation: "Buxton, that of great name ſhalt be, for hote and holſome baine, / Farewell, for I perhaps ſhall not thee ever ſee againe").

It was not only Mary Queen of Scots who used St Ann's Well in the late 16th century, however. Several members of Queen Elizabeth's Privy Council appear to have taken advantage of the fact that the Earl of Shrewsbury owned accommodation there, and the Earl of Leicester, Lord Burghley, and the Earl of Sussex all made use of the Buxton water. Robert Dudley, the Earl of Leicester, appears to have begun using the water on the advice of physicians. Gilbert Talbot, in a letter written to his father, the Earl of Shrewsbury, in the July of 1576, mentioned that "the fysitions hathe fully resolved that whersoever my L. of Lecester be, he must drynke & use Buxtons water XXth dayes together". Robert Dudley certainly made use of the Earl of Shrewsbury's accommodation, as another letter written by Gilbert Talbot in 1578 warns that "my L. of Lecester thretenethe to cum to Buxtons this sum-er". In fact, Queen Elizabeth, despite her strongly Protestant standpoint, seems to have endorsed use of St Ann's Well, and she herself wrote to the Earl of Shrewsbury and his wife on the 15th of June, 1577, to thank them for allowing Dudley to stay at the Old Hall:

|

To Our right trustie & right welbelovid Cousin and Counsellor th' Erle of Shrewsburye, and to or dere and right welbelovid Cousin the Countesse, his wyfe Our very good Cousins, Being geven t' understand from or cousin of Leycester how honnorably he was not onlie latelie receaved by you our cousin the Countesse at Chatsworth, & his dyet by you both discharged at Buxtons, but also presented wth a very rare present, we should do him great wronge (houlding him in that place of favor we do) in cace we should not let you understand in howe thanckfull sorte we accept the same at both your hands, not as don unto him but to or owne self, reputing him as annother our self; and, therefore, ye maie assure your selves that we, taking uppon us the debt not as his but or owne, will take care accordingly to discharge the same, in such honnorable sorte as so well-des-rving creditors as ye are shall nevr have cause to thinck ye have met wth an ungratefull debtor... Geven under or signet, at or mannor of Greewch the XXVth day of June, 1577, and in the XIXth yere of or raigne. Your most assured lovinge Cousin and Soverayne, ELIZABETH R. |

When Lord Burghley decided to journey to Buxton, to bathe his "old crased body", in the summer of 1577, he also stayed at the Old Hall. He seems to have successfully obtained a cure, and the Earl of Essex wrote to Lord Burghley shortly after his visit, to "heare what good successe you have hadd by the bathe of Buxtons". A few years later, on the 7th of August, 1582, the Earl of Sussex wrote to Lord Burghley and described his ongoing treatment at Buxton:

|

I have no thing to wryte from this barren soyle but to make you acquaynted wth that tocheth my self in this my jerney hether. I fownd the well so cold, by reason of the ill wether, as I cowld not but very syldome have use of goyng in to it: The water I have dronke lyberally; begyning wth thre pynts, and so encreasyng dayly a pynt till I come to VIII pynts, & from thens dessendyng dayly a pynt till I shall ageyne reterne to III pynts, wch wilbe on Thursdye next, and then I make an ende. Mr Atslowe hathe good hope I shall receyve muche good hereby, & I alredy feele sumwhat; the reste tyme wyll shewe. I do mene to reterne wthin two or thre dayes after I shall make an ende of my drynknyng, but wth some more leysure then I came hether, for so my state requyrethe aftr this bayne. |

By the final decade of the 16th century, pilgrimage to St Ann's Well had regained such popularity that an act was passed, in the 39th year of Elizabeth's reign (either 1596 or 1597), containing a clause stating that "none resorting to Bath, or Buckston Wells, should beg, but should have relief from their parishes and a pass under the hands of two justices of the peace, fixing the time of their return".

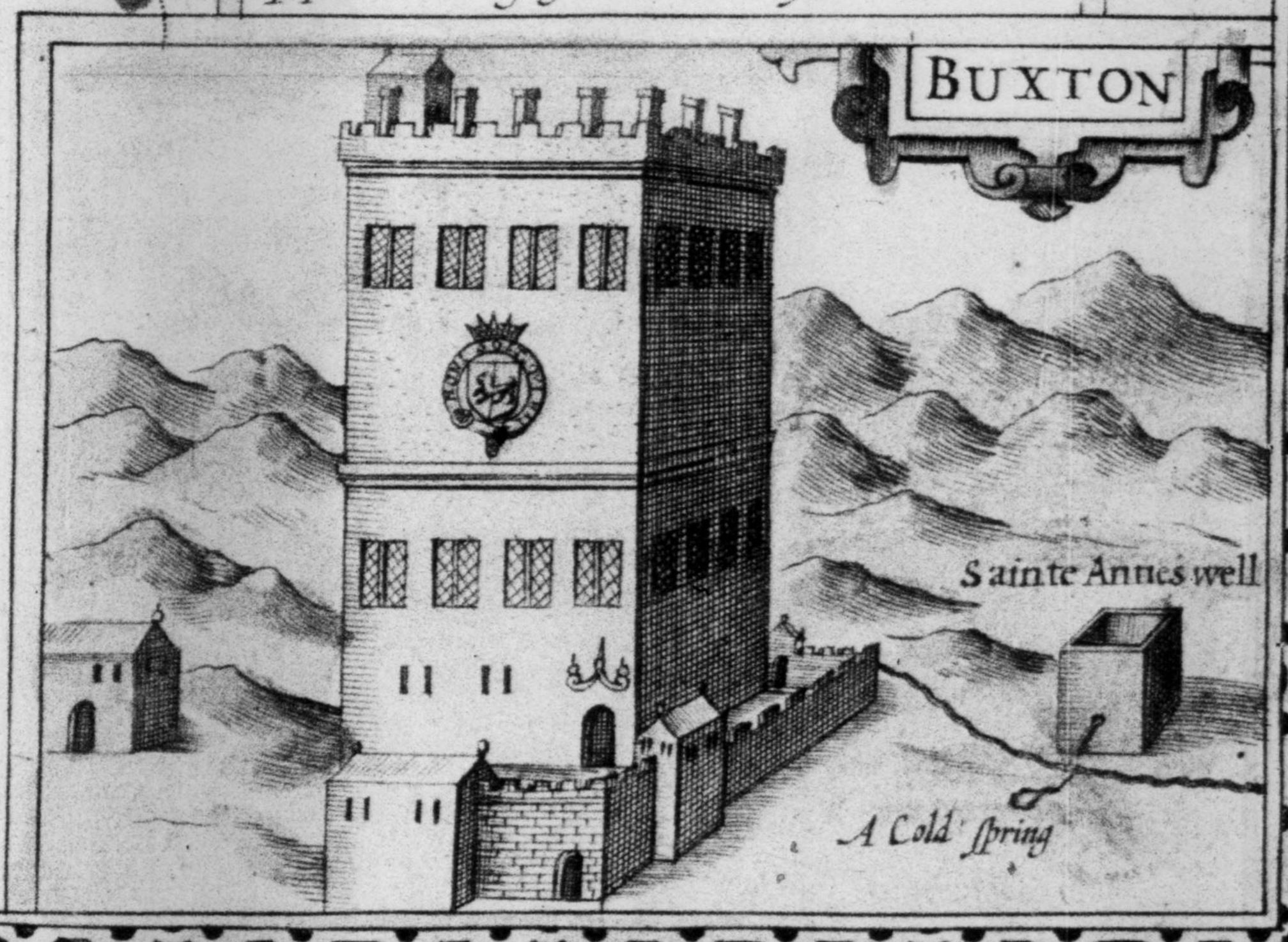

Shortly after this, John Speed published the only surviving illustration of both St Ann's Well and Buxton Old Hall in his Theatrvm Inperii Magnae Britanniae (1616). It clearly depicts the old Roman wall that once surrounded the bath:

|

Although Speed's illustration did not depict this, other descriptions of the well and baths from the early 16th century specifically mention the site being covered by a roof of some description. Thomas Hobbes toured the area around Buxton in 1626, and he published, in 1636, De Mirabilibus Pecci, a Latin poem that described what he called "the Seven Wonders of the Peak"; these included St Ann's Well. The poem was translated into English in 1678 by an unidentified "Perſon of Quality", and published as De Mirabilibus Pecci: being the wonders of the peak in Darby-Shire, commonly called The Devil's Arſe of Peak:

|

The Sun burnt clouds but glimmer to the ſight, |

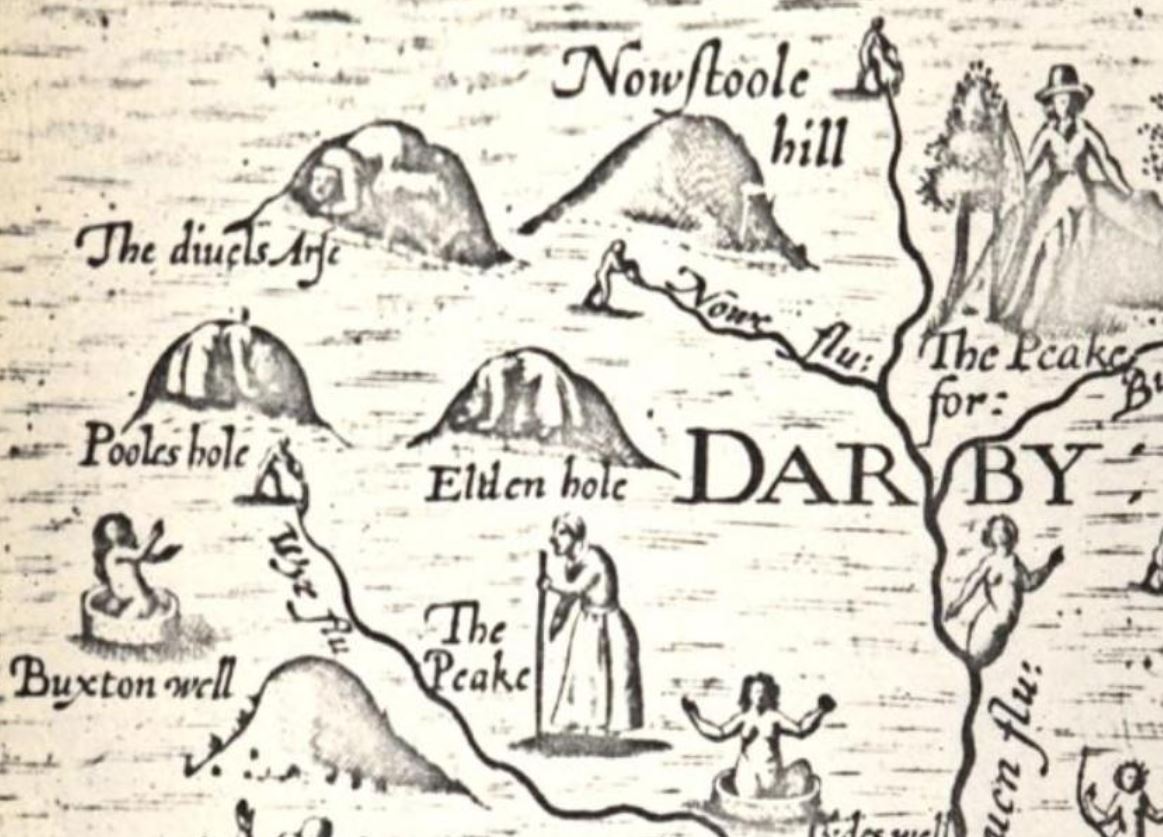

The 17th century saw, if nothing else, a large amount of poetry written about the well, and, in 1622, Michael Drayton's Chorographicall [sic] Description of all the tracts, rivers, movntains, forests, and other Parts of this Renowned Iſle of Great Britain (which he had "Digeſted into a Poem"), included both a versed description of Buxton and a map of Derbyshire that marks "Buxton Well"; it is only really the map that is of any interest:

|

In 1670, the Old Hall that had been constructed by the Earl of Shrewsbury, around a century earlier, was demolished and replaced with a newer, larger building by the Earl of Devonshire, William Cavendish. By this time, the Hall was used for accommodation by all eminent and wealthy visitors to Buxton, and Thomas Short described the New Hall's facilities in his Natural, Experimental, and Medicinal History of the Mineral Waters of Derbyshire, Lincolnshire, and Yorkshire (1734):

|

And Mr. Taylor of the Hall, upon his own Expences, keeps a very good pack of Hounds, for Gentlemens Diverſion, as alſo a pleaſant warm Bowling Green planted about with large Sycamore Trees; and in the Houſe a fine Engliſh and French Billiard Table. A little Eaſt of St. Annes Well, over the Ditch or Level which carries the warm Water from the Bath, is made a curious natural hot Bed, and upon the reſt of this Canal might be made the fineſt Greenhouſe in the Northern Kingdoms; he has alſo taken in ſeveral new Gardens with planting, and ſeveral curious Walks. The Garden Stuff has a peculiar, grateful Flavour; up one pair of Stairs in the Hall is a beautiful dining Room, ſeventeen Yards long, and nineteen Foot Wide, ſeven other entertaining Rooms, eleven lodging Rooms with ſingle Beds and Cloſets, twenty nine other lodging Rooms; this one Houſe affords ſixty Beds for Gentlemen and Ladies, beſides ſuitable Accommodations for their Servants and all other proper and uſeful Offices. |

It was during the first decade of the 18th century that the well was significantly re-modelled. In 1709, Sir Thomas Delves, who had received a cure at St Ann's Well, and who wished to express his thanks, had the Roman wall destroyed, to make way for a new arch over the spring. John Campbell, in his Political Survey of Britain (1774), described this new arch, the inside of which was "ſet round with Stone Steps", as being "twelve Feet long, and as many broad". The old stone basin also seems to have been replaced, with a new "Stone Baſon two Feet ſquare".

By this time, Buxton seems to have regained (or perhaps even surpassed) its medieval fame, and the esteemed physician Dr John Floyer, writing in The Phyſician's Pulſe-Watch in 1707, attested that he had "caus'd Buxton Water to be carry'd in Bottles forty Miles" to "Country-Men", so that "they might have the benefit of Bath Waters near Home". The list of ailments that Floyer claimed could be cured by water from St Ann's Well differs slightly from the list given, almost two centuries earlier, by John Jones, and included "Vomitings", "want of Appetite", "pains in the Stomach", "comſumptive Coughs", "ſcorbutic Itchings in old Perſons", "Stone", "Scurvy", "Hiſterical" cases, "Aſthmatic" cases, "Gouty" cases, "all Defluxions", and "hot Tempers".

At this point, physicians with an interest in analysing the properties of various springs and water sources began to take notice of St Ann's Well, and it was subject to several strange tests and experiments. For example, George Pearson, an eminent physician of the late 18th century who had a strange obsession with what he called "the permanent Vapour that extricates itſelf from Buxton-Water", published an account of a very odd and rather gruesome experiment that he had performed using water from St Ann's Well, in volume 2 of Observations and Experiments for Inveſtigating the Chymical History of the Tepid Springs of Buxton (1784):

|

The Effects of the above Mixtures on Animals, related in the following Experiment, ſhew further the Reſemblance between them and the permanent Vapour obtained from Buxton-Water ſubected to a boiling Heat. Exper. XXXI. Into a Receiver containing two Ouce Meaſures of the Mixture N° 2. of laſt Exper. ["A Mixture of two Meaſures of this permanent Vapour of Buxton-Water, and one Meaſure of Air"] was introduced a Mouſe. This Animal lived without apparent Uneaſineſs four Minutes; - it then had a Shortneſs of breathing and ſtarting with Protruſion of its Eyes; and in four Minutes more it expired. Into the ſame Receiver containing two Ounce Meaſures of the Mixture of N° 1. of laſt Exper. ["a Mixture of equal Quantities of the permanent Vapour that riſes ſpontaneouſly from Buxton-Water and common Air] a Mouſe was conveyed. It lived ſeemingly without Pain for ſix Minutes then ſhewed Signs of Uneaſineſs, and died with its Eyes appearing as if ready to ſtart out of its Head. |

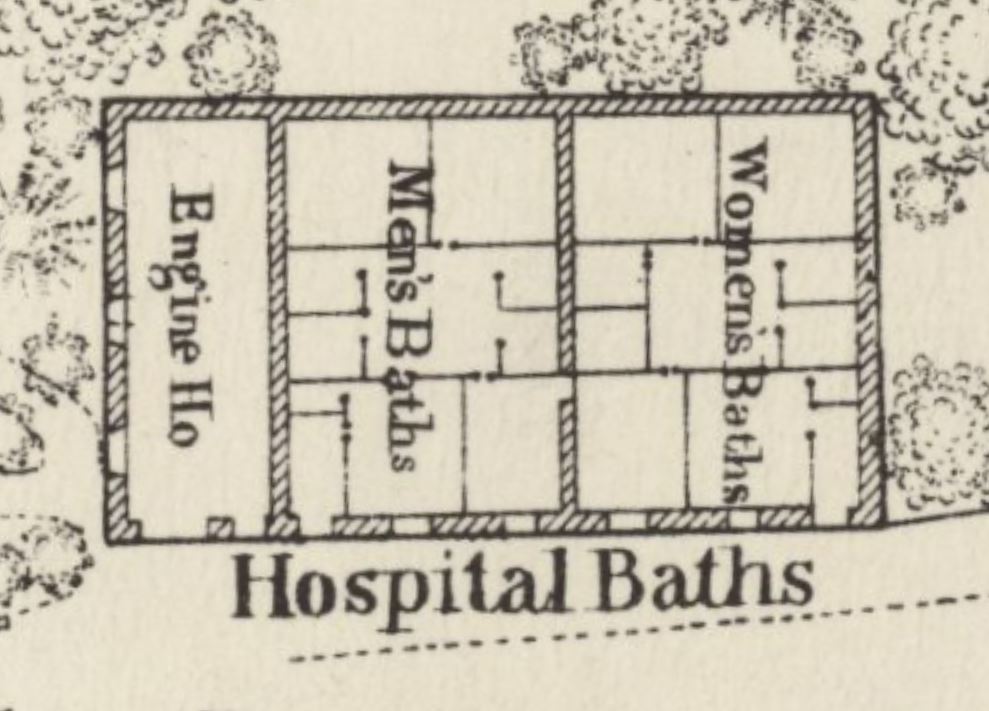

In 1779, the Buxton Bath Charity was founded, which served to enable the poor to visit Buxton and use the baths. Occasionally, they would give their lower class patients a small portion of money to be spent during their time in Buxton. Of course, the rich gentry who used the baths did not want to mix with the lower classes, so it appears that a set of "charity baths" were created for the sole use of the poor. According to William Henry Robertson, writing in A Guide to the Use of the Buxton Waters (1867), between the years of 1820 and 1838, 12,608 of the Charity's patients were cured, out of the 14,906 patients aided by the Charity; and, between the years of 1838 and 1858, 16,575 patients were cured, 5,859 were partially relieved of their ailments, and 885 experienced no improvement, out of a total of 23,319 patients aided by the Charity.

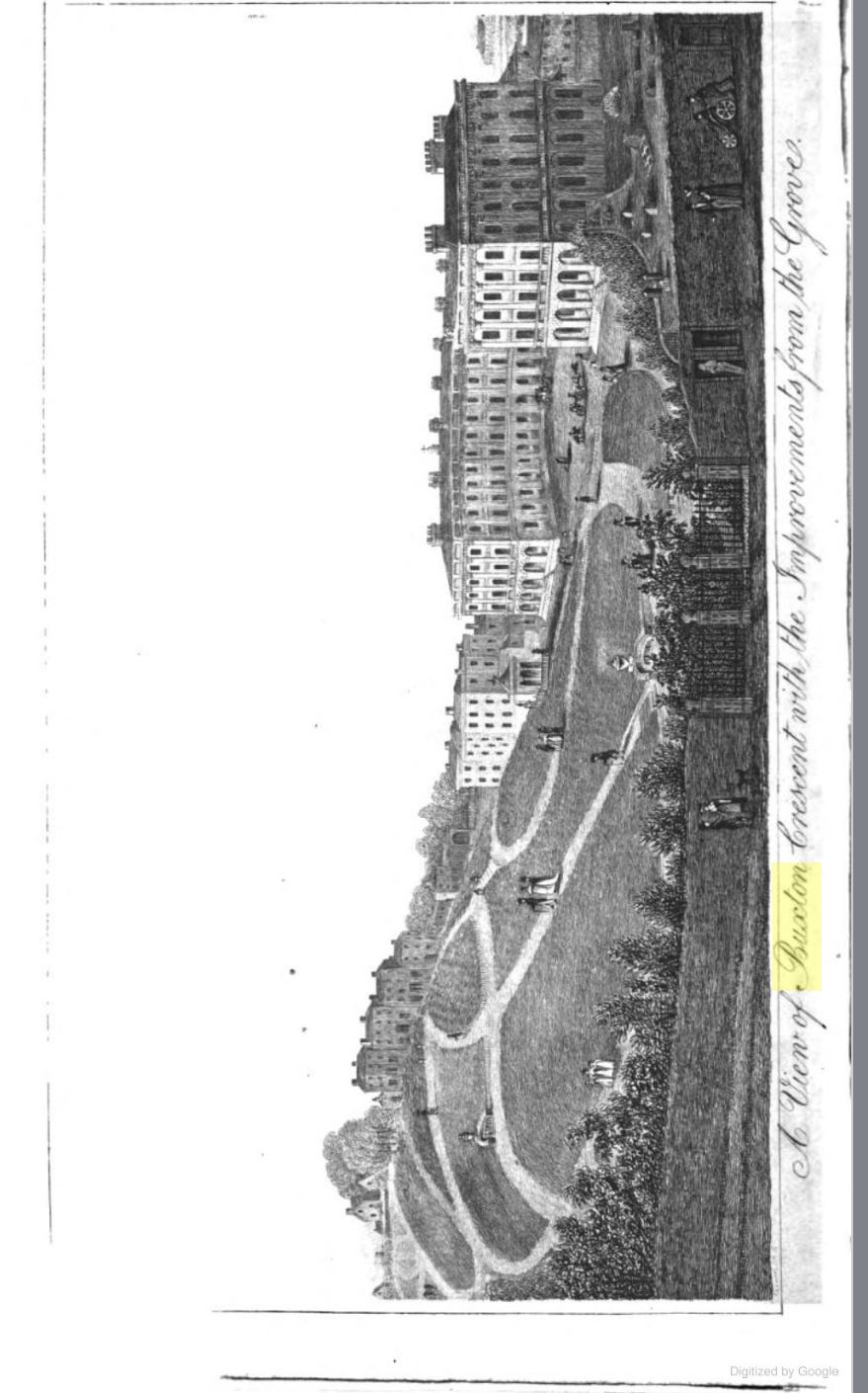

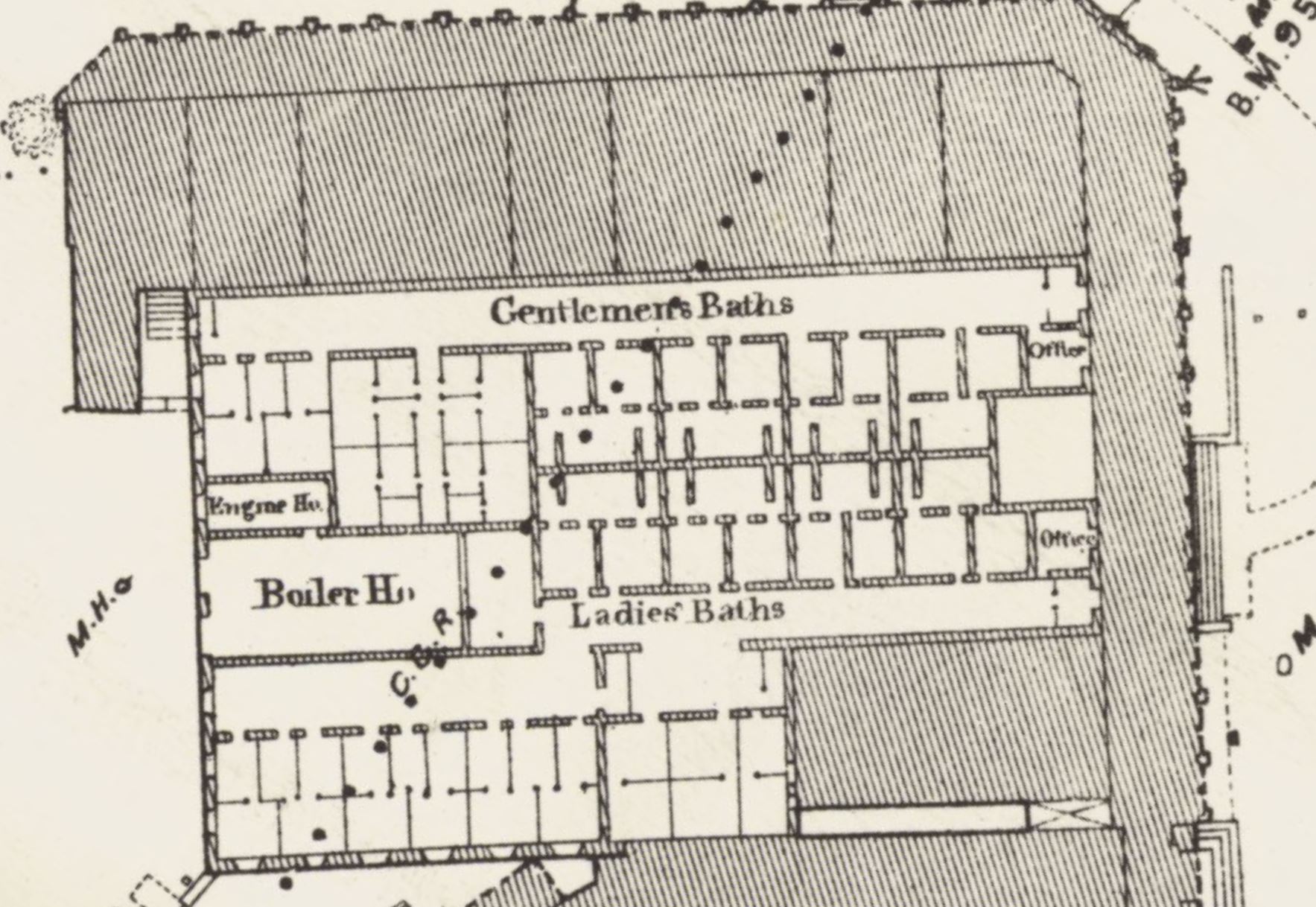

St Ann's Well only became more popular during the early 19th century, and, in around 1820, a new bathing complex was constructed to the north-west of the well. These baths possessed the latest technology regarding the so-called "water cure", and were described in The New Buxton Guide in 1823:

|

There have been erected, within these two or three years, very convenient and elegant hot baths, at the opposite end of the Crescent to the other baths, adjoining the Piazzas, whereby the visitors can walk under cover to either baths. There are select apartments for ladies, and also for gentlemen, with convenient dressing-rooms; and to these are added, an improved machine for pumping on the patient, with more effect; also vapour and shower baths, on a new and improved principle. The baths are lined with white marble, and there are machines contrived for adjusting the temperature of the baths, which convey cold or hot water. The water is the same as the other baths, only heated by steam, to avoid producing any important change in its nature, which might have been effected in the common mode; and hence, in many cases, these heated baths may be expected to produce a more essential benefit than common heated water. |

|

|

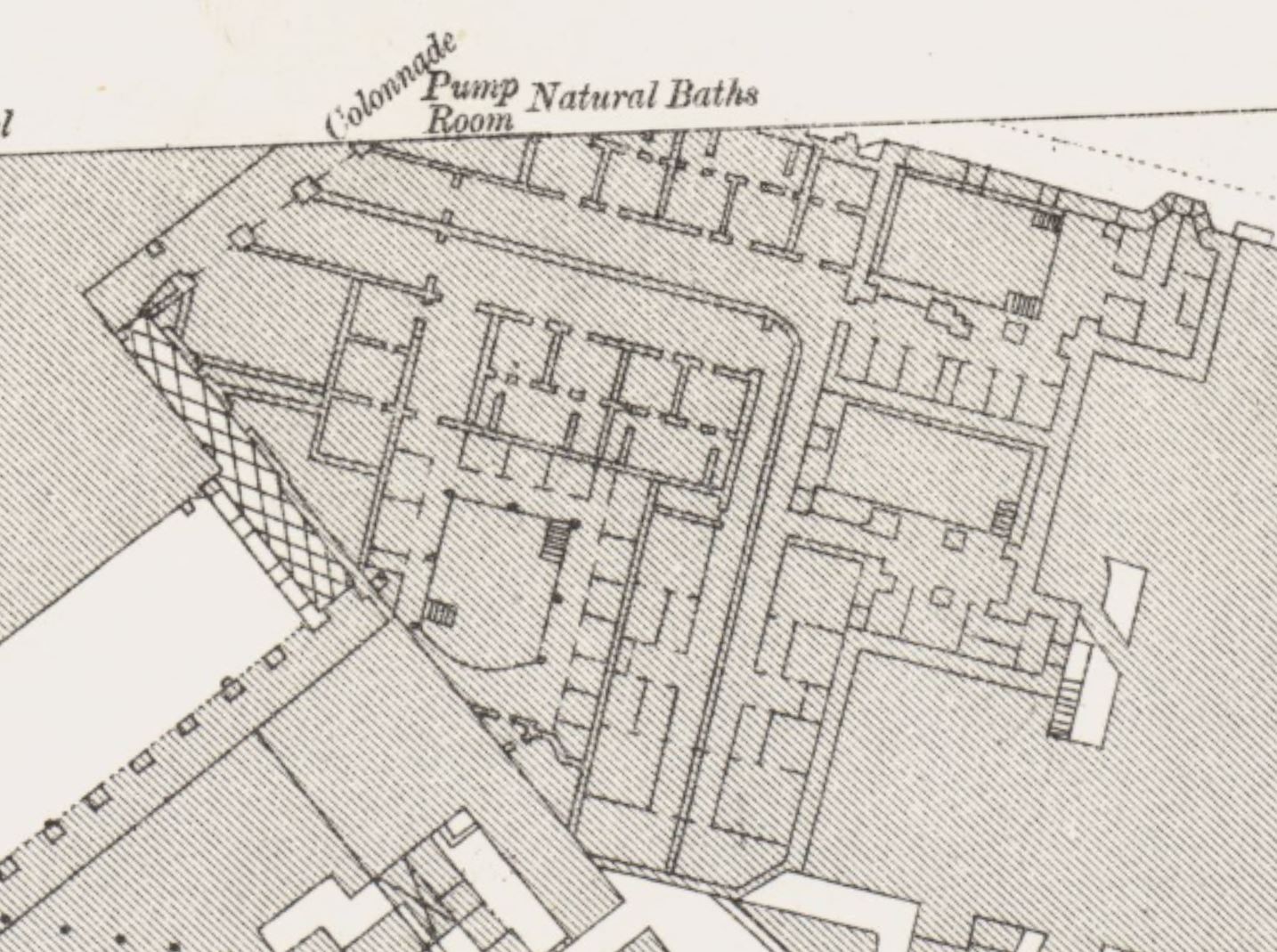

By the early 19th century, a multitude of baths existed in Buxton, all of which were reputed to be good for curing different ailments. On the eastern end of the Crescent were the hot baths (as just described), whilst the western end was home to a set of cold baths, which were termed the "natural baths". There were five, according to a certain Dr Scudamore, writing in 1839, of these "natural" baths: three for "gentlemen", and two for "ladies". In addition, Scudamore attested that there was a "vapor bath", several "well-constructed shower baths", "an excellent plunging bath of the temperature of 60°", the two "charity baths", and the "large bath", which was reputedly located directly over the spring.

|

|

|

In fact, Dr Scudamore was something of an expert on the water cure at Buxton. He described several instances of cures obtained through the use of Buxton water in a series of books on the subjects of gout and chronic rheumatism, published in the very early 19th century. Perhaps the most notable example of these supposed cures is that of a "gentleman" who suffered from gout, and who visited the well annually, in order to maintain the cure that he had obtained:

|

A gentleman, who had been several times attacked by gout, not in the severest degree, visited Buxton with much advantage; and, anxious to adopt all the means of prevention of his disorder, resolved on returning every year to the springs, so long as he should find success in bathing. Accordingly he presented himself to St. Anne and the baths every season for seventeen years. He omitted the eighteenth year; the charm was broken, and he had again a fit of gout; since which he has renewed his homage at the shrine of health, as regularly as before, and with the same success. |

In 1852, a new structure was built on top of St Ann's Well, the earlier structure that it replaced presumably being that which was built by Thomas Delves in 1709. This, however, did not last very long at all, as it was completely replaced again in 1895; the drinking fountain from 1895 is depicted on this Victorian postcard:

|

Even as late as 1892, Buxton was still incredibly popular. In the June of that year, the Buxton Local Board Act was passed, which allowed the Local Board for the District of Buxton to accept the building of a new pump room as a gift from the then Duke of Devonshire, Spencer Compton Cavendish. According to the Act itself, a new pump room was desperately needed, as the older one was "small and inconvenient and inadequate to accommodate the inhabitants of the district and the public resorting thereto for the purpose of drinking the mineral waters". Building work seems to have been completed in 1894.

However, both Buxton and St Ann's Well shortly began to decline in popularity, as the so-called "water cure" fell out of favour. Nonetheless, many of the Victorian features of the spa town still remain, although the current drinking fountain was constructed in 1940. The building that once housed the hot baths, at the eastern end of the Crescent, has been turned into a small shopping centre, and dubbed the "Cavendish Arcade" (nonetheless, much of the original tiling and one or two of the hot baths survive); the pump room from 1894 exists in its entirety; and the Hall (on the site of the Old Hall) survives as the "Old Hall Hotel", although in a much altered form.

|

|

|

|

Access: The well is located at the side of a public road. |

Images:

Old OS maps are reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

Copyright 2025 britishholywells.co.uk